Wexner Center for the Arts

By Gregg Bordowitz

ROBERT BECK’S RECENT EXHIBITION, “dust”-organized by the Wexner’s Bill Horrigan-seemingly affirmed two contradictory positions: On the one hand, each piece in the show required the discipline of psychology as the methodological basis of its interpretation. On the other hand, each work refused any coherent psychological reading whatsoever. In this way, Beck’s work avoids clichkd interpretations while at the same time handling the very substance of creative labor.

Consider a group of small, framed, meticulously crafted works on paper. They seem to be examples of drawings produced in art therapy; indeed, all of these works, called Untitled, have parenthetical explanations of their source material-e.g., Untitled (“Psychological Evaluation of Children’s Drawings” by Edith M. Koppitz/”The Artist as Therapist” by Arthur Robbins), 200112004. Among these drawings, a few sheets of paper retain their torn edges, as if they have been ripped directly from a spiral-bound notebook. Typed onto and sometimes directly over the lines of the drawings, the clinical notes – , of an observing psychologist neatly annotate the efforts. In some cases, handwritten lines are scribbled over t v ~ e d , . notes. Defeating the hierarchy of observation between doctor and patient, diagnostic interpretations and patients’ marks are assigned the same status. Beck conflates the results of two or more differing psychic processes. Separate interpretations revolving around the same events find their final form collaged into one expressive document.

A suite of five large photographs from 2004 occupied one wall. All are titled Screen Memory, with the parenthetical titles Family Room, Sister’s Room, Brother’s Room, Father’s Room, and Mother’s Room. Memories of home become stand-ins for family members, as each photograph contains a different dense, grainy accretion of overlaid images-a sailboat, a unicorn, the American flag, an eagle, geese, Jesus. Like Freud’s description of the unconscious, Beck’s photographs are spaces where the laws of time and physics do not apply. Many objects can rest in the same place at the same time.

The key to the exhibition was a painting on a bathroom partition. Standing in front of Untitled (Clean), 2004, facing the shiny surface, the viewer expects to see his or her reflection. That expectation is defeated. The steel surface, hung slightly higher than eye level, has a limited reflective capacity. The work of art promises to return the viewer’s reflection, and it fails. But is the term failure appropriate? Perhaps the work refuses to return the viewer’s image. Which does it do, fail or refuse? The painted and scratched marks on the surface of the metal do not aid the search for the self. A phallic graffito floats loosely detached in the composition. Whose cock is it-the artist’s. the viewer’s, the painting’s? We attribute intention to a work of art. As makers or beholders, we have feelings about what the object is trying to say, what it does to us and for us.

On another wall, a very large drawing, titled Hidden Pictures (Between Two Deaths). 2006-2007. refers to a . . page from the children’s magazine Highlights. A legend provides a list of “hidden objects” placed where they fit most invisibly within a field of squiggly line drawings. Beck’s Hidden Pictures are recovered, separated from the chaos of the game, yet they still do not yield interpretations. Instead, they just hang there, suspended on the picture plane. In Beck’s rendition the hidden objects take the foreground, and their context becomes deemphasized. Everything apart from the identifiable objects is amalgamated into one gray mass. The substance of this mass is the urgent issue of Beck’s work.

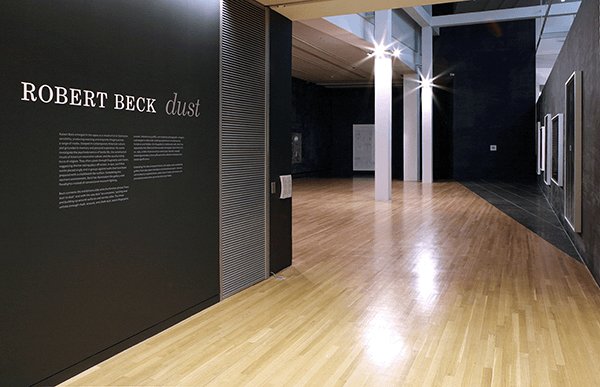

The walls of the exhibition space were treated with a matte, blackboardlike finish. Upon each slate-colored wall, chalk texts had been written and erased, from the very top to the bottom of each wall. An analogy was made between a school and a museum. The energy of lessons taught and erased permeated the space. The content of the curriculum matters less than the very fact of its institution as a process. The walls of the lobby outside Beck’s exhibition were also painted black, and everyone was invited to draw whatever they wanted. Inviting viewers to draw on museum walls is not radical. It can’t bring down the walls, nor will it destroy the alienating social relations that erect authority. However, the gesture of granting license to the creative potential of each museum visitor must not be dismissed. An ethical question arises: Who grants license to whom? If we perceive that the artist himself is the granting authority. we have merely reproduced the authority of professionals. If we grant that art itself is a constituting principle vested with the authority to license the creative potential of every individual’s desire, then we face a moral challenge. This requires belief akin to religious devotion.

“Dust” is about mood, the mood of religion. Not any articular religion but the common property of all beliefs: faith. Belief in reality requires faith that each thing has a place and a purpose and a maker. We have faith in the existence of a thing, faith that the thing is the product of intention, faith that everything has an origin. We believe these things in spite of what we know: Nothing belongs to a certain place. Nothing possesses a specific purpose. And nothing derives from one sole creator. Art teaches us all that. How? Dust is both a noun and a verb. As a thing. -, it covers; as an act, it reveals. The most significant feature of dust is that it lies everywhere.

A WRITER AND ARTIST, GREGG BORDOWlTZ IS CURRENTLY A VISITING PROFESSOR AT THE ACADEMY OF FINE ARTS, VIENNA.

.png)