By A.M.Homes

Is it evidence? Read between the lines. In a nation addicted to armchair investigation, it won’t be long before jury duty is something served at home in front of the TV set, the verdict reached by pressing either a guilty or not guilty button on the remote control. Reflecting on our increasing need to judge for ourselves, Robert Beck’s “true crime series” is part homage to the photo insert found in mass-market, “fact-based” paperbacks and part addition to a growing body of art based on documenting all the grisly details – what might be called “evidentiary art.”

Beck’s series is made up of four major pieces: November Spawned a Monster, 1993; The Tail Gunner’s Vulgar Revenge, 1994; The Cornfield, 1994; and a set of brown “evidence” bags and boxes sealed with tape that reads “WARNING SEALED EVIDENCE: DO NOT TAMPER,” containing pillow, light-bulb, boots, and boy’s pajama top, with a Polaroid of the evidence affixed to the outside. November Spawned a Monster, 1993, consists of fourteen 6 ¾ - by 4 ¼ inch pages with one or two – either fabricated or appropriated – captioned photographs on each page. Page one: photo of suburban house captioned “9109 Bengal Road, Randallstown, MD (police photo).” Below it a photo of the seminude body of a young man – dead, one supposes, in an alley captioned “Mike Nolan (prosecution exhibit).” The photos continue: “Bobby, age 7 (Defense exhibit, Family photo albums),” grave marked “Christopher Paul Beck, Dec. 26, 1957 – June 20, 1965” (the brother?), ACT-UP demonstration, two men standing under a tree, male body, sixth-grade class photo, The Bar NYC, motel in Maryland, shirtless man in chair, salesman, bridge-club Halloween party, body of Robert Beck, suburban Maryland living room, Christmas 1968, male in underwear (face down, arms bound, gagged), Maryland State Police Crime Laboratory, Eastern Maryland Farm, man leaning against a tree, plastic bag with Frankenstein book, four sailors, high-school-yearbook photo, backyard shed.

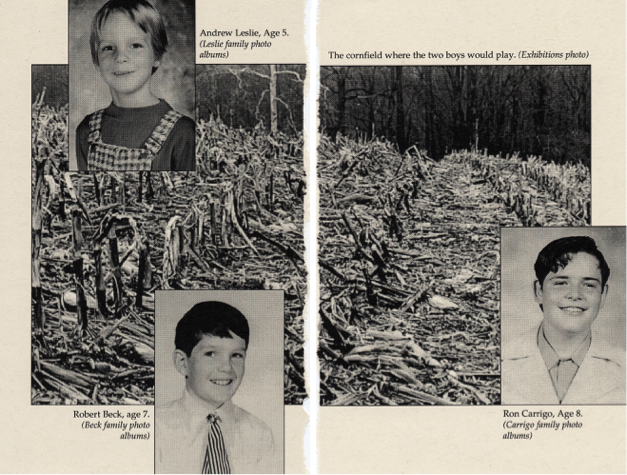

But where does all this lead? Back is investigating not only criminality but also issues of identity – gay identity. While much homoerotic imagery focuses on unarticulated possibility, these photos read as though they were taken by asexual investigator. The lack of any erotic charge encourages the viewer to take the lead, to investigate the pictures with his/her own narratives of crimes of passion or prejudice. Who is the victim, the perpetrator, and what is the difference between them? Underscoring the precariousness of the construction of identity, the young boys depicted in these school photos could be anyone: you, someone you know, neighbor, friend, brother, etc. When school photos are shown – whether flashed on TV during the nightly news or gracing the back of the milk carton at breakfast – there is always that tragic subtext, one that seems to encompass the fluidity of identity, the Everyman quality of children, and the youthful face full of promise and hope, threatened by an adult world seemingly poised to take action against it. The Cornfield, 1994, takes fullest advantage of the possibilities: a two page spread, with school-type photos of three young boys set over a harvested, skeletal cornfield proves more haunting than Beck’s extended series, which ultimately suffer from an absence of affect, almost begging for Sargent Friday or Colombo to come in and lay down a solid storyline.

In Beck’s work, the uncanny sense that something has happened is less present in other evidentiary projects such as Luc Sante’s Evidence, 1992, and Joel Sternfeld’s “On This Site…” where the viewer is either confronted with hard evidence – the bloody body at the crime scene – or a narrative describing the nature of the crime. Opting for what remains enigmatic in the criminal, Beck leaves the viewer somewhat at a loss. Perhaps it is here that the greatest strength of the work lies: the state of confusion and ignorance into which Beck plunges the viewer implies that the ability to read the piece, to order the images, the events – to reconstruct the crime – is a sign of privileged knowledge… of guilt.

https://www.artforum.com/inprint/issue=199502&id=57363§ion=new-york

.png)