Dia Center for the Arts, New York, NY

September 15, 2008

Video: Robert Buck on Andy Warhol a

NOTE: A few months after I changed my father’s name by a single vowel, as a work or act of art, Lynne Cooke invited me to present an “Artists on Artists” lecture. I could now identify with Warhol “to the letter”. I researched, wrote, delivered, and revised this paper, for possible publication in 2009, before I was fully awake to the magnitude and radicality of the teachings of Jacques Lacan, especially the later Lacan. He maintained, as do those in the contemporary Freudian Field, that the artist always precedes the analyst in his “knowledge” of the unconscious, James Joyce being the exemplar. To frame my reconsideration of Warhol with the object “clinically” was naive. However, the wager to recalibrate Warhol’s achievement via his speech- and language-based works was not in vain. Here, as an aritist writing in the art university discourse, my ambition was to contribute something new to the wealth of Warhol studies. June 29, 2017

Andy Warhol a

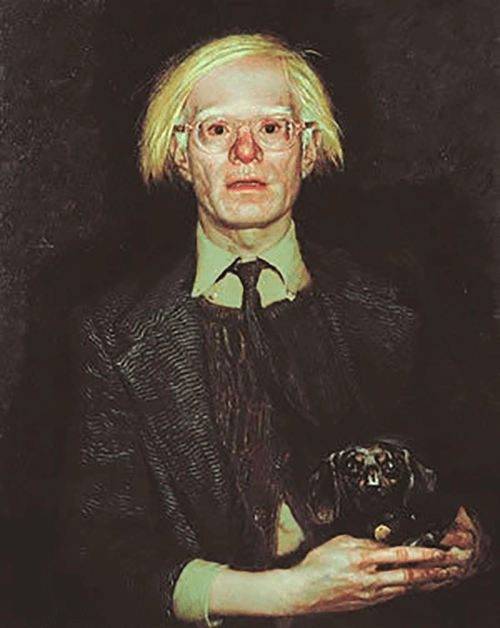

Warhol. Warhola. What if we take Warhol as his word, and consider his acts of writing as a viable means by which to index his visual art? My proposal is that Warhol’s encounter with language was traumatic [as it is for us all], and the consequences ramify as a unifying trait that underwrites his art. And with reference to the teachings of Jacques Lacan, namely his interpretation of the writings of James Joyce, I want to insinuate that Warhol was psychotic, an “ordinary psychotic” 1, who for this reason exemplifies our time, with its waning status of the Father. It was the voice that guided me.

“The Letter! The Litter!” This giddy exclamation from “Finnegan’s Wake”, cited by Lacan for its various connotations -- offspring, gurney, straw bedding, an absorbent granulated clay for cats, a correspondence, refuse – reverberated as I contemplated the reams of writing devoted to Warhol. (To paraphrase Lacan, what is a hole if nothing surrounds it?2 ) It echoed again as I considered Warhol’s own “writing”, eighteen volumes in all, always co-authored, including illustrated promotional booklets, novels, and a magazine, “inter/VIEW”. And again it resounded as I trailed the letter littered from his last name, for although Warhol may have forgotten the letter, the letter did not forget Warhol.

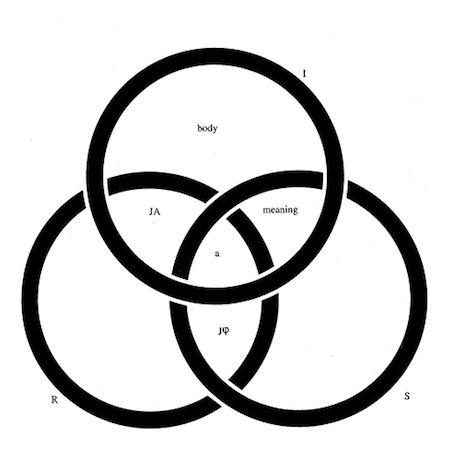

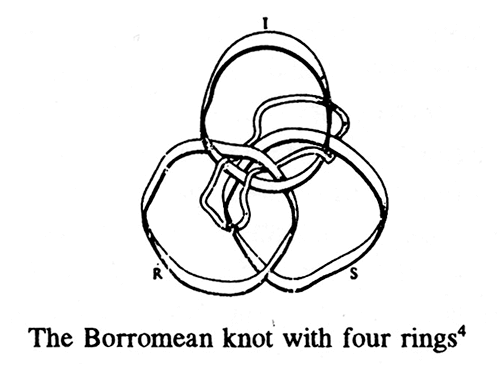

Two basic concepts of Lacanian psychoanalysis are prerequisites for my reconsideration of Warhol. First, Lacan’s founding thesis, following his “return to Freud”, is that the unconscious is structured like a language. It is composed of differential elements, signifiers and signifieds, and abides by the laws of metonymy and metaphor3. Second, Lacan introduces three structural orders or realms, the Imaginary, the Symbolic, and the Real. He later illustrates the ways in which they are intertwined by utilizing the Borromean knot as a topology, a non-metaphorical means to formulate the interaction of the Symbolic with the other two realms. Later, after his encounter with the writings of Joyce prompts a reconsideration of his earlier extrapolation of Freud’s Oedipus Complex and, consequently, an elaboration of his own the Name-of-the-Father, he will add a fourth ring, called sinthome. 4

Warhol: “If you want to know all about Andy Warhol, just look at the surface: of my paintings and films and me, and there I am. There’s nothing behind it.5” Lacan: “The signifier is what represents the subject for another signifier.” 6

objet a

It was the lower-case “a”, one relevant to both Warhol and Lacan, that beckoned me. The folly to willfully mistake the letter “a”, purloined, allegedly by chance, from Andy Warhol’s surname, for the “a” of autre, French for other, as cause to reconsider his art qua writing by way of Lacan’s objet petit a, proved exceptionally rewarding7. In Lacanian algebra there are two letter “a”s: the lower-case “a”, the abbreviated object little a, and an upper-case large “A”, big Other. In the topology of the Borromean knot, objet petit a is located at the center, where the three rings intersect.

Considered his greatest invention, objet petit a is intentionally defined abstractly by Lacan as an elusive yet contingent element. Consequently, attempts to define it unambiguously, even within psychoanalysis, are appropriately foiled. The following synopsis, an amalgam of explanations found in writings from the Lacanian school, is no exception.8

The human being is taken in by language, and objet petit a is the result, the excessive remainder, the retroactive “cause”. It is that which is missing from the signifying chain but paradoxically that which also masks this absence. As a residual yet structural place within the chain, it becomes the basis of the structure, and constitutes the subject, and with it desire. As a kind of signifier-in-absentia, it is the lost object, albeit one that was never there to begin with but is retroactively installed has having had to have been lost so as to conceal the empty place. It is an evanescent, positive waste that accommodates itself to the lack in the Other. (As the subject is forged by others in language, Other also connotes the chain of signifiers, knowledge, and the unconscious.) It is that bit of the Symbolic that gets snagged by the Real. And it is here that an unbearable, traumatic, excess of enjoyment, or jouissance, accumulates.

Object little a is something that drops away as result of the alienation of the subject within language. Essentially, it is a real thing, a part object, separable from the body, designated originally by Freud as breast and feces. Through its consequential relation to lack, it is the object cause of desire. It typifies Lacan’s definition of the speaking subject as “want-to-be”, at once being-as-lacking and being-as-desiring. He later links it with semblant, asserting that it is a semblance, or facsimile, of being. Objet a is consolidated via the drives, which haul the part objects. To those defined earlier by Freud, Lacan adds gaze and voice, and these pertain most specifically to Andy Warhola.

“A Is an Alphabet” is Warhol’s first illustrated promotional book and the first time the invisible vowel reappears. (Its full affect will insist fourteen years later with “a: a novel”.) In his seminar on Edgar Allen Poe’s “The Purloined Letter”, Lacan traces the itinerary of a letter, a correspondence that operates as object a. It is both the undisclosed contents of the letter and the play of inter-subjective relationships it engenders that concern Lacan. “The purloined letter is synonymous with the original radical subject of the unconscious. The symbol is displaced in its pure state: one cannot come into contact with it without being caught in its play. […] When the characters get hold of this letter, something gets hold of them and carries them along. At each stage of the symbolic transformation of the letter, they will be defined by their position in relation to this radical object. This position is not fixed. As they enter into the necessity peculiar to the letter, they each become functionally different to the essential reality of the letter. For each of them the letter is the unconscious, with all of its consequences, namely that at each point of the symbolic circuit, each of them becomes someone else.”9

He recognizes in the triadic replays of the narrative structure the basis for the insistence of the signifying chain and, via the boomerang-like path of the letter itself, repetition automatism, or the return of the repressed. He delineates the prolonged, detoured trajectory of the letter with the phrase en souffrance (in sufferance), a French postal term for an unclaimed letter or one awaiting delivery. “If the letter may be en souffrance, they [the characters] are the ones who shall suffer from it. By passing beneath its shadow, they become its reflection. By coming into the letter’s possession -- an admirably ambiguous bit of language -- its meaning possesses them.” 10

Warhol a

Here is Warhol, interviewed, along with Ivan Karp, about the errant “a”: “Well, the reason why I dropped the ‘a’ is that ‘cause when I was going around with a portfolio, it just happened by itself.” Ivan Karp: “People just forgot to put it on. Right?” Warhol: “Yeah. So, it just happened. There were other Warhols in the telephone book, and… ah…” 11

“By 1953, Warhol had changed his name from ‘Warhola’ and had discontinued an affected variant ‘André Warhola,’ though he acquired several nicknames, including ‘Raggedy Andy’ (because of his calculated appearance) and ‘Andy Paper Bag’ (because of his practice of carrying a paper bag in place of a portfolio).12” He later considered again changing his name to John Doe and Morningstar, according to Jackie Curtis and Ultra Violet respectively.13 It is not insignificant that André, which he donned to affect sophistication, and signed as if in French, was the correct Carpatho-Ruysn pronunciation of his father’s name, Ondrej, Andrew in English. Warhol later drops this nomination, choosing instead one made by mistake to his Rusyn name by an American art director, a woman, Tina Fredericks.14 Occurring appropriately enough by happenstance, this is Warhol’s answer to Joyce’s question “How Am I To Sign Myself”15 , one that is tellingly inverse to his mother Julia’s infamous mangling of the English language.

As we know the name games did not stop once the “a” dropped away. For, as has been often recounted, Julia, would often sign Andy’s name to his illustrations. And if she was too tired, Nathan Gluck, Warhol’s assistant at the time, would. According to Joseph Giordano, an advertising director and friend to both Julia and Andy, on occasion she would even claim herself to be Andy Warhol: “So, she came in and slammed the suitcase on the ground and she turned around. She looked at him and she said ‘I am Andy Warhol.’ And there was a big discussion about why she was Andy Warhol. But, I guess, she convinced him that he was. So, you see, I… I can only work from Missy’s influence on Andy, really, because I’ve only seen him in circumstances with Missy, really.”16

Of course, lack is not lacking until it is named as such, and it may not have accrued to Warhol, in the guise of surface and void, if he had not cut-out a space for it. By displacing the “a”, into the Real as it were, Warhol betrays its emptied place as a master signifier, one that coordinates a position for the rest. Precisely through its absence does he disclose it as a signifier of “over-plus”, as Joyce writes, brimming with jouissance, beyond pleasure, and one thus unable to be linked into the signifying chain. So, what Warhol edits, in turn, returns to edit him; “a” for augmentation: sanded nose, skin creams, pinhole glasses, girdles, wigs. Erased, the blank place left open by the letter “a” ex-sists as a unifying trait.

Warhol, not Lacan, might well have famously said “Man’s desire is the desire of the Other.”17 This recalls the often repeated anecdote in which Warhol, formerly Warchola18 , shows two Coca-Colas19 , painted renditions of the bottled brand, to Emilio de Antonio in the early 1960s to ask which, dirty or clean, he prefers. Relevant to the well-known outcome of this “taste” test was the appearance of Warhol’s deference to the Other as a trademark strategy.20

Language / Writing

The letter A is not only the first letter of the 26-letter English alphabet but of the 36-letter Rusyn Cyrillic alphabet as well, and the only letter of the twelve common to both to coincide sequentially. Rusyn, also known as Carpatho-Rusyn, is an East Slavic language, with six dialects, including Lemko, which the Warholas spoke at home in Pittsburgh. Carpatho-Rusyn shares a linguistic lineage with Russian, Belarusian and Ukrainian.21

“Julia Warhola never was ‘Americanized’. She remained loyal to her Czech roots all her life. She attended the Byzantine Ruthenian Catholic Church, the faith of her ancestors, oftener than just for Sunday mass. She spoke Czech in the home and taught it to her sons. The older boys, Paul and John, tried to speak it on occasion to please her, but Andy rejected it, and if she ever spoke to him in her native tongue, he answered in English. This was the earliest evidence of Andy’s commitment to all things American. But when Paul and John were small, very little was spoken around them but Czech, and their efforts to speak it left them with ‘funny accents’, causing other children to mock them, and their speech had to be ironed out into flat American during their school years.”22 While Andy Warhola may have succeeded in rejecting any outward trace of a funny accent, as an adult he and Julia would converse privately in Rusyn, according to several Factory denizens. This bilingual rapport is not unusual for the children of immigrants.

“Warhol distrusted language; he didn’t understand how grammar unfolded episodically in linear time, rather than in one violent a-temporal explosion.23

“Andy Paperbag went to Carnegie Tech and majored in pictorial design. During his first year he flunked out […] because of his traumatic relationship with the written word. The adult Andy Warhol became a prolific author and memorable aphorist (‘In the future, everyone will be world-famous for fifteen minutes’); these successes have obscured the fact that he could not write. The inability went further than the mere dependence on ghostwriters (unexceptional in the annuals of celebrity authorship) would suggest: he avoided ever writing anything down. I found virtually no correspondence in his hand. […] Clearly he was dyslexic, though undiagnosed […] Some of his errors: ‘vedio’ for ‘video’; ‘polorrod’ and ‘poliarod’ for ‘Polaroid’; ‘tailand’ for ‘Thailand’; ‘scrpit’ for ‘script’; ‘pastic’ for ‘plastic’; ‘herion’ for ‘heroin’; and ‘Leory’ for ‘Leroy’. He had a hard time with simple English.”24

Warhol’s relationship to language was fundamentally unsound. Consequently his work is riddled with words -- caption, copy, label, logo, how-to, headline, name-brand. His ultimate defense against language, the tape-recorder, was also a deceptively humdrum yet novel means by which to render, via transcription, the materiality of speech, to capture the voice as object – call it an invocatory writing.

Radio / Voice

Radio became popular in the home after being developed for communication purposes in World War I. In 1920, the first commercial radio station in the United States, KDKA, was established surprisingly enough in Pittsburgh. By1922, the first regular entertainment programs and advertisements were broadcast. The medium proliferated, and evolved into what is commonly referred to as the “golden age of radio”, dating from 1935 to 1950. Coca-Cola, Campbell’s Soup, Jell-O, and Kellog’s were among the most prominent advertisers of the era.25 Andy Warhol was born in 1928.

“I had three nervous breakdowns when I was a child, spaced a year apart. The attacks – St. Vitus Dance – always started on the first day of summer vacation. I don’t know what this meant. I would spend all summer listening to the radio and lying in bed with my Charlie McCarthy doll and my un-cut-out cut-out paper dolls all over the spread and under the pillow.”26

The bouts of St. Vitas Dance, which in this passage from his autobiography “THE Philosophy of Andy Warhol” he earmarks as symptom, and as much for the near-hysterical misnomer “nervous breakdowns” he assigns to them as for the atypical allusion to a possible meaning or cause, occurred when he was eight, nine, and ten. The scenario repeats itself: bed ridden while recovering from a “nervous breakdown”, Andy Warhola is comforted by the radio.

While much has been made of Warhol’s recollections of his Charlie McCarthy doll, its importance as an incarnation of the object-voice has been underplayed. A popular radio figure of the day, Charlie McCarthy was Edgar Bergen’s dummy. They were on the air from December 1937 to July 1956. The ironic popularity of a ventriloquist on the radio, where the trick of “throwing the voice” goes unseen, may be explained as a phenomenon of the fascination for the new medium itself. It is as if the dummy existed solely to personify the disembodied voice of radio, to situate what otherwise could have been experienced as eerie auditory hallucinations.

Two other radio programs of the era were comic books, “Dick Tracy”, which was on the air for a decade beginning in 1938, and “Popeye the Sailor”, which ran from 1935 to 1938. And another program became a Pulp magazine, “The Shadow”. Originally “The Detective Story Hour”, it was re-branded due to the popularity of its mysterious narrator. From 1937 to 1954, The Shadow had “the power to cloud men’s minds.”

(Fade up on ominous-sounding organ) “Who knows what evil lurks in the hearts of men? …The Shadow knows!” (Sinister laughter; fade out on organ) 27

And on December 9, 1938, at the end of the eighteenth show of “The Mercury Theater of the Air”, Orson Welles announced the shows new sponsor, the Campbell's Soup Company. The series moved from Sunday to Friday and the name was changed to “The Campbell Playhouse”. It was on the air through 1946. Most stories were based on classic books, but popular movies were also adapted. Ad copy for one of the Campbell’s Soup commercials reads as follows:

(Fade up on sunny melody) “Not so many years ago, tomato soup and cream of tomato were unusual dishes enjoyed very much, but not very often. Today, of all the soups in the world, tomato soup is the one most often served. Not because women have taken to making tomato soup frequently; no, on the contrary, few housewives ever attempt it anymore. There’s just one reason for tomato soup’s popularity, and it is this: the magic, matchless flavor of Campbell’s Tomato Soup. There’s a lively verve, a dashing zest about this flavor that people take to at once and come back to and enjoy again and again. The first racy taste of it has a way of arousing a desire to eat, and yet there’s a pleasant feeling of satisfaction when the last spoonful is gone. So this soup is a happy choice for the main dish at lunchtime or at supper, and it also is a fine way to start the day’s main meal. Serve it sometimes, too, as Cream of Tomato, made with milk instead of water. You can always be sure that it will be received with pleasure, because this, of all soups, is the one people like to have most often – Campbell’s Tomato Soup.”28

Interrupting the Carpatho-Rusyn Slavic spoke in the Warhola Pittsburgh home was the English language voice of American commercial radio. Although speech behaves differently by language, voice, which buoys it, does not.

Jacques-Alain Miller’s elucidation of Lacan’s formation of the voice as object a is instructive, and I quote him here at length: “The voice appears in its dimension of object when it is the Other’s voice. In this respect, the voice is the part of the signifying chain that the subject cannot assume as ‘I’ and which is subjectively assigned to the Other […] The voice comes in place of what is properly unspeakable about the subject, what Lacan called the subject’s ‘surplus enjoyment’”, also know as jouissance, the locus of objet petit a.

The “voice is precisely that which cannot be said […] We do not use the voice; the voice inhabits language, it haunts it […] Speech knots signified – or rather the ‘to be signified’, what is to be signified – and signifier to one another; and this knotting always entails a third term, that of the voice […] The voice is everything in the signifier that does not partake in the effect of signification […] What Lacan calls voice is akin to intonation and its modalities. [Lacan] implies that it is not just the signifying chain as spoken and heard, but also written and read.29

“Words troubled and failed Andy Warhol, though he wrote, with ghostly assistance, many books, and had a speaking style that everyone can recognize because it has become the voice of the United States – halting, empty, breathy, like Jackie’s or Marilyn’s, whose silent faces sealed his fame.”30

Tina Fredericks describes meeting Warhol: “He had a breathy way of talking. His voice was slight, un-emphatic, whispery, covered over with a smile. When you read his writings, you can almost hear him speaking in that voice.”31

Psychoses / Name-of-the-Father

The psychotic speaks as if language were coming not from inside but from outside. Lacan’s writing on the psychoses radically modified the clinical discourse and treatment of psychosis, and revised the conceptual relationship between subject and voice, drive and object.

The Name-of-the-Father is a cornerstone of Lacan’s psychoanalytic teaching and evolves throughout his career. He interprets the Oedipus Complex in terms of a metaphor because it involves the primary function of substitution; abruptly put, the Name-of-the-Father for the desire of the mother. It is designated as the paternal function because, via the signifier, it institutes Oedipal prohibition.33 Retroactively, it is the preeminent metaphor and guarantees the possibility of all other metaphors and, consequently, the ability to create new ones. As the fundamental master signifier, it allows signification to proceed normally. It confers identity on the subject, naming and positioning him or her within the Symbolic order. The connection between signifier and signified is at best precarious, and any discord can lead to a radical separation of the two chains unless they are bound at anchoring points. A number of these cinches are essential for a subject to coalesce and achieve normalcy. In neurosis, there are certain points of attachment that temporarily halt the incessant sliding between signifier and signified.

Conversely, when they are absent, or come untied, psychosis can result. Here, the paternal metaphor is foreclosed, like a non-admissible piece of evidence within a court of law. This malfunction tears a hole in the Symbolic order and imprisons the subject in the Imaginary realm, which predominates in psychosis. What prevails linguistically as a consequence of foreclosure is metonymy.34 The psychotic’s experience is plagued by the constant metonymic slippage of the signified beneath the signifier, which forestalls fixed, reliable signification. Thus the phenomena most apparent in psychosis are disturbances of language, for instance, holophrases, portmanteaus, and neologisms.

With signifier unmoored from signified, the signifier itself becomes the object of communication. Hence, signification is distributed between code phenomena, or language, and message phenomena, or meaning. Foreclosed, a signifier can disruptively appear where it should not, “outside” within the Real. There it produces moments in which “objects, transformed by an ineffable strangeness, are revealed as shocks, enigmas, significations”35. The psychotic believes in these auditory hallucinations or emanations, known as elementary phenomenon, with a near fanatical conviction and certainty.36 One purpose of the paternal metaphor, the Name-of-the-Father, is to avert the onset of such delusions.

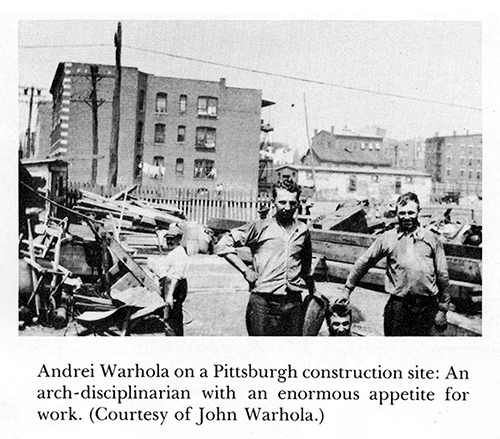

Warhol’s father, mostly absent from home according to his autobiography, died when Warhol was not quite thirteen. As the story goes, Warhol, unable to bear the sight of the dead father, laid out in the living room in keeping with Greek Catholic tradition, hid beneath his bed until the his father’s body was removed days later.37

A search through innumerable Warhol biographies and chronologies yielded only one photograph of his father, in the Victor Bockris biography. Even there the caption does not readily identify him as one of the four men pictured.

From A to B and Back Again

In “THE Philosophy of Andy Warhol: From A to B and Back Again” the voided “a” returns so forcefully as to reduce Warhol to the letter itself. “I wake up and call B. B is anybody who helps me kill time. B is anybody and I’m nobody. B and I. I need B because I can’t be alone, except when I sleep. Then I can’t be with anybody. I wake up and call B. ‘Hello, A…’”38 The telephone, a fixture in Warhol’s life, literalizes, here literally, the A-to-B-and-back-again relay.

From the “Love (Puberty)” chapter of “A to B and Back Again”: “My father was away a lot on business trips to the coal mines, so I never saw him very much. My mother would read to me in here thick Czechoslovakian accent as best she could and I would always say ‘Thanks, Mom,’ after she finished with Dick Tracy, even if I hadn’t understood a word. She’d give me a Hershey Bar every time I finished a page in my coloring book.”39

If meaning was suspended, detoured, or misconstrue due to the indeterminacy of English by way of Carpatho-Rusyn, something else became the communicative mortar between mother and son, which this passage and the earlier one about summers spent listening to the radio, intone. This bond is the newly emergent “voice” of commercial radio, which transmits American popular culture of the 1930s to their Pittsburgh home.

Warhol, in this recounting of the anecdote forty years later, ciphers an attempt to establish a borderline by first responding to Julia’s thick Slavic accent in English with “Thanks Mom”. The only bit of dialogue quoted in the chapter, it ripples with a corresponding “but no thanks Mom”. This boundary is fortified with the signifier Hershey Bar, deciphered, following Lacan, to the letter, as her-she-bar, or here-she’s-barred. (As far as I know, with the exception of T-shirts created in 1979, and there as only one brand among a few, the Hershey Bar surprisingly never achieved iconographic status in Warhol’s work -- or not so surprisingly as the case may be – as if by association it too was barred.) I leave to the reader the pleasure of interpreting the other pop cultural artifact littered here, Dick Tracy.

Later, in the same chapter: “But I didn’t get married until 1964 when I got my first tape recorder. My wife. My tape recorder and I have been married for ten years now. When I say ‘we’, I mean my tape recorder and me. A lot of people don’t understand that. The acquisition of my tape recorder really finished whatever emotional life I might have had, but I was glad to see it go…”40

Warhol does not mention what others do. He had purchased a tape-recorder previously for Julia in the mid 1950s. She uses it to record herself signing Rusyn folk songs and then to sing-along with herself in playback.41 So Julia too spoke the same language, from A-to-B-and-back-again. Another not insignificant detail from her biography, for the affect it must have lent to Warhol’s illnesses, was the death of her first child Justina before she immigrated to America in 1921, following her husband by nine years. Reportedly, she would watch Warhol sleep for fear that he would die.

Other examples of the A-to-B-and-back-again circuit mother and son seemed to share, ones that all too well illustrate Lacan’s observation that ultimately “the signifier is posited only insofar as it has no relation to the signified,”43 include:

Julia, from “Holy Cats by Andy Warhol’s Mother”: “Some pussies up there love her; Some don’t; Some like it day; Some like it night; Some talk to angels; Some talk to themselves; Some know they are pussy cats so they don’t talk at all; Some play with angels; Some play with boys; Some play with themselves; Some don’t play with nobody…” 44

Warhol, from John Hallowells’ 1965 book “The Truth Game”: “Favorite tie, favorite pickle, favorite ring, favorite Dixie Cup, favorite ice cream, favorite hippie, favorite record, favorite song, favorite movie, favorite Indian, favorite penny, favorite feet, favorite fish, favorite saint, favorite sin, favorite Beatle…” 45

Warhol’s 1966 advertisement in The Village Voice: “I will endorse with my name any of the following: clothing, AC-DC, cigarettes, small tapes, sound equipment, Rock ‘n Roll records, anything, film and film equipment, Food, Helium, WHIPS, Money – Love and Kisses, Andy Warhol”46

Unable to proceed to metaphor, the psychotic idles somewhere between the first and second signifiers of the chain, somewhere along the way from A to B. Psychoanalytically speaking, somewhere between alienation and separation. “This [malfunction] initiates an intransitive: ‘It means/it wants to say’; an unaccomplished signification, enigmatic emptiness […] degree zero of signification -- soon to be doubled by an ‘it means/wants to say something’ – signification of signification […] where the certainty of the subject that it is implicated in its being through this phenomenon is anchored.”47 Lacan, from his seminar on the psychoses: “The subject knows that what is said concerns him, that there is some signification, although he does not know which one.”

Gaze

Although Lacan introduced “The Mirror Stage” in 1936, the concept, like other foundational ones, evolved throughout his career.48 By the early 1950s, he no longer viewed the mirror stage simply as a formative stage of ego identification and self-consciousness, a product of a child’s jubilant but false assumption of its reflected, illusory image as self. Rather, he deems it a permanent and integral structure of subjectivity, a paradigm of the Imaginary order. In the early 1960s, he makes a critical revision when he stresses the role played by the Other and the voice, exemplified by the mother’s speech, and reiterates the conflictual nature of the dual relationship it establishes. By then he observes that “The plane of the mirror is governed by the voice of the Other”; the gaze is indexed by the voice; and, provocatively, “the gaze is the underside of consciousness.”49 In short, it is the voice that bisects the plane of the mirror and animates the specular realm.50 Via the mirror stage, Lacan synthesizes voice, correlative to gaze, as objet a. “The objet a in the field of the visible is the gaze.” Gaze is not understood as sight but as the place from which the subject is seen by the other, which is everywhere. Within the gaze, the best one can expect is to appear as a stain.

When it does appear, the power of the gaze can be mortifying. In 1976, Andy Warhol and Jamie Wyeth agreed to paint portraits of one another, an anomaly in Warhol’s career. Their comments betray the stakes of the gambit: ANDY: “Jamie was a very difficult subject; I don’t know why. I took more pictures of him than anyone else. It took two months of thinking about.” JAMIE: “I just felt a rapport. I knew it was something I wanted, the minute the idea came up. I see this portrait of Andy as a sort of portrait of New York. I love New York and I feel this is New York. ANDY: I wasn’t concerned about how he would paint me. I think it’s great. It’s so realistic I can’t believe it.”52

Warhol’s characteristically canny response again approximates Lacan: “When, in love, I solicit a look, what is profoundly unsatisfying and always missing is that – You never look at me from the place from which I see you. Conversely, what I look at is never what I wish to see.”53 If the comparison of the two portraits is compelling, it is due to how graphically apparent Warhol’s desire is to tame the gaze, to disarm it, dompte-regard as Lacan writes it.

Warhol / Joyce

To cleave Warhol to Lacan’s later re-inscription of Joyce, specifically the epiphanies – those passages of found words Joyce inserted into his writing -- as symptomatic of psychosis and the enigmatic experience, I offer the following few passages from essays devoted to Lacan’s encounter with Joyce. To better appreciate the startling similarities, exchange Joyce’s name and references to his writing, for Warhol’s and his art.

“Joyce described the process of his literary creation. He collects words from shops and posters, from the crowd that walks past him. He repeats them to himself over and over so that in the end they lose their signification for him.

These words read, heard, present themselves in the dimension of the elementary [phenomenon] detached from any signification. The word becomes the thing that it is. Joyce raises the mutation of the letter into litter to the dignity of an epiphany. Lacan defines the epiphany as a direct knotting of the unconscious to the real and says, ‘the formidable creative power of Joyce stems from the fact that he is not held back by any connections that the letter has with the Symbolic and the Imaginary. He is in relation with a letter that has severed all its identifications, which is not attached to any stable signification.’” 54

“The epiphany marks an uncanny coincidence of insignificance and signifying tautology, at once the evacuation and the over-determination of meaning.” 55

“For the definition of the epiphany does not simply lie at the level of an isolated experience, but also in the very act of writing it down. And it is this act that ultimately allows Joyce to reassert a relation to the Other without passing via fantasy in the normal neurotic way. In fact, in the epiphany Joyce succeeds in knotting speech, the Symbolic, directly to the letter, the Real, thereby reducing his experience to the reality of the knot in a rigorous act which, through its dual aspects of transcription and transmission, founds the certainty of his aesthetic mission” 56

Lacan’s work with Joyce culminates in the mid-1970s with Seminar 23, “Joyce and the Sinthome”. The origin of the term sinthome is alternately cited as an earlier spelling of the word symptom, and a Joyce neologism, which rings, saint, sin, Thomas, homme, synthetic, home, and so on.

Seminar 23 “explores what we could call the enigma of Joyce. Lacan’s Joyce is a psychotic subject, but one who never has the symptoms of a full-blown psychosis […] The issue of stabilization then becomes paramount -- how does Joyce achieve this? […] Lacan returns to his old notion of imaginary compensation from Seminar III as he describes how Joyce’s ego, as a writer, allowed him to make a name for himself, and compensate for the foreclosure of the Name-of-the-Father […] Lacan argues that foreclosure is represented by a break in the three-ringed Borromean knot of Imaginary, Symbolic and Real – a failure of knotting, but one which can be compensated for with a fourth ring – in the case of Joyce, the ego, his writing – which, like the earlier concept of imaginary compensation (the ego, of course, is imaginary), will allow the structure to hold together, without falling apart […] Lacan rewrites psychic structure as a four-ringed Borromean knot, in which it is the sinthome, as the fourth ring that holds the other three together. Furthermore, the sinthome is nothing other than a general form of what used to be the Name-of-the-Father, which is now but one possibility as a type of sinthome, a possible fourth ring […] With this final shift, all of the earlier clinical formulations are recast. But, the key to this re-casting, is to realize that Joyce’s case – originally seen as exceptional, unusual, and very particular given his very singular place as a writer – is not the extraordinary one. We must invert this organization completely. Joyce’s form of psychosis is rather an ordinary one, one that perhaps resembles neurosis.”57 That psychosis is essentially “ordinary” to every subject is a revolutionary development in Lacan’s teaching, one he denotes with characteristic precision with his amended term the “Name(s)-of-the-Father.”

Painting / Transcription

In hindsight, Warhol’s knack for naming, and name-dropping, is symptomatic of the “all sizzle and no steak” age of advertising, and the rise, in the wake of World War II, of consumer culture. The evolution of the commodified, now “liquidated”, signifier – no longer carried aloft by voice but televised as image -- is announced by the Soup Cans. The contiguous serial canvases – soups change, brand doesn’t – seem to slide metonymically, culminating in their true signification, which is to show just how ruthlessly the signifier stuffs the signified, like a turkey, as Lacan says. A-to-B, but always back-again.

Forecasting what Rainer Crone called Warhol’s panel-paintings58, the cans, taken together, especially as a grid as they are often exhibited, are redolent of icon-screens, the wall that separates the sanctuary from the nave in the Greek Catholic Church. Formally akin to comic books, the sequential frames of the pictorial grids infer a message or a narrative and, reciprocally, a being received or “read”. Yet perilously free of captions or thought bubbles, they risk slipping their connotative bearings. The influence on Warhol of the formal aspect of the iconostasis litters Warhol scholarship. Yet a secondary aspect, call it an injunction to interpret, exerted an equal force. Perhaps Warhol could not write, but he could “read”. “It means, it wants to say something.”59

Can his paintings be construe as acts of writing? Can they more effectively, and critically, be appreciated as transcriptions, from A-to-B, his means progressing technically from blotted line, to stamp, to opaque projector, to silk-screen? Can Warhol coded as “writer” -- the tape-recordings, the books, the voice portraits of “inter/VIEW”, (and, arguably, the films and videos) -- bespeak this possibility? Like Joyce’s epiphanies, Warhol’s “icons” reappear from the “outer space” of American popular culture; apparitions (neither photograph nor painting), cultural litter, visual holophrases -- we encounter them as indefinite articles, codes in search of messages. “The signification of signification itself.” 60

A-to-B-and-Back-Again. The images stammer, echo, stutter, falter, pile-up, with no means of crossing the bar to metaphor. Instead, as a consequence of code divorced of meaning, signification stalls and the life-blood of the images congeal before our eyes, transmogrified as icons, mute and enigmatic.

It’s as if each pass of the squeegee struggles, in its differential procedure, to find the proper tone or modulation, the right pitch or inflection, as if voice were in search of speech, or as if we had a sudden vision of the surface of language. Does not the automatism of repetition cycle the failure of the signifier to “properly” signify and, simultaneously, register the troubled excessive enjoyment it insists on?

With reference to the late work, specifically the Camouflage paintings, do they quiet the language disturbances recorded by the earlier work? For here the repetitive nature of the imagery mirrors the readymade fabric print, allowing Warhol’s silk-screen grid process, now clean not dirty, to hide within the mimicry pattern of the resulting canvas. Put otherwise: Did the voice find speech? Did the letter at last arrive at its destination, as it always does?

Conclusion

There are three critical ways in which we may have denied knowing Warhol: he was not Czechoslovakian, but Carpatho-Rusyn, a nationality with a different dialect, history and cultural heritage;61 the influence of commodity culture on his art is more accurately sited in the “golden age of radio”, rather than 1950’s advertising culture exclusively; and his essential relationship to the gaze is inflected by the voice-object.

Perhaps citizen Warhol’s “Rosebud”, the purloined letter “a”, the semblant, can be apprehended finally as the-Name-of-the-Father, Warhola, Ondrej, André, namesake, ab-sense, sinthome.62 As Lacan says, “One can do without the Name-of-the-Father on condition that one makes use of it.”63 Once Warhol signed without the “a”, the blank that remained functioned “litterally” as object a. By de-inscribing a letter “a”, one that heralds all the eventual affectations and augmentations, Andy Warhola made a name for him self and became his own cause. Warhol-the-symptom.64

And Warhol’s symptom may cipher our own, as he foreshadows the capitalization of enjoyment, part of a wider distillation process in which the entropic nature of surplus enjoyment is converted into pure value, like labor before it. “Surplus value is nothing else but the waste or loss that counts, and the value of which is constantly being added or included in the mass of capital. […] The total is increasing, and this is called accumulation of capital. What makes this accumulation possible is, as Lacan puts it, that the surplus enjoyment starts to be counted. The entropic element [of enjoyment] is itself transformed into value and added as supplement. […] In this discourse, it is no longer knowledge that is being detached from the entropic element of work/enjoyment, it is this very entropic element itself that is being detached, in the name of knowledge and value, from its own entropy or negativity. What is being exploited and squeezed in every imaginable way is now precisely our enjoyment as an immediate source of surplus value.”65 As James Joyce wrote long ago in “Finnegan’s Wake”, “iSpace”.

With his ordinary psychosis, Warhol heralds the twilight age of the Father, the “shift from the Ideal to the object a as the organizing point of identification; the rise of the discourse of the capitalist; and the shift from the discourse of the master to the discourse of the analyst itself as the key organizing discourse of society today.” Warhol ciphers the son that the passing of Freud's Father, Oedipus, precipitated – in the Names-of-the-Father and thus of the son.

© 2008-09 Robert Buck

* This text was originally presented on September 15, 2008 as part of the Dia Art Foundation Artist on Artist Lecture Series. I am grateful to Lynne Cooke for the opportunity to formalize and present my ciphering of Warhol with Lacan. Todd Alden, with characteristic generosity, shared with me his trove of Warhol publications and ephemera, and this galvanized my research. My understanding of Carpatho-Rusyn ethnography and Slavic dialects benefited appreciably from conversations I had with Dr. Paul Robert Magocsi. For publication purposes, I revisited my original text to cite references and to amend what only time can reveal, in the endless process of revision, to be, dare I write, lacking.

Notes

1. “Jacques-Alain Miller said in September 1998: ‘From the moment there is a diversification of norms, we are evidently in the era of ordinary psychosis. What is coherent with the era of the Other that does not exist is ordinary psychosis.’ In particular, Miller notes that, in contrast to the triggering of classical psychosis, in cases where ‘the subject has elaborated a sliding, drifting symptom, there is no clear-cut triggering.’” Thomas Svolos, http://www.lacan.com/ParisEnglishSeminar.html.

2. Jacques Lacan, The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis, Jacques-Alain Miller, ed., Alan Sheridan, trans. (New York, London: W.W. Norton & Company, 1981), p. 115.

3. Jacques Lacan, “The Function and Field of Speech and Language in Psychoanalysis” in Écrits, Bruce Fink, Héloise Fink and Russell Grigg, trans. (New York, London: W.W. Norton & Company, 2006), pp. 197-268.

4. Before adding the fourth ring, Lacan privileges the three registers alternately throughout his teaching. Milestones in this evolution include, Jacques Lacan, The Seminar of Jacques Lacan, Book II: The Ego in Freud’s Theory and in the Technique of Psychoanalysis, 1954-55, Jacques-Alain Miller, ed., Russell Grigg, trans. (New York, London: W.W. Norton, 1993); Jacques Lacan, Le Séminaire XXII, R.S.I., 1974-75, transcribed by Jacques-Alain Miller in Ornicar?, Nos. 2-5; and Jacques Lacan, Seminar XXIII: Joyce and the Sinthome, Luke Thurston trans., unpublished.

5. Gretchen Berg interview with Andy Warhol, The East Village Other (November 1, 1966), reprinted in I’ll Be Your Mirror: The Selected Andy Warhol Interviews, 1962-1987, Kenneth Goldsmith, ed. (New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, 2004), p. 90.

6. Jacques Lacan, “The Subversion of the Subject and the Dialectic of Desire in the Freudian Unconscious” in Écrits, pp. 671-702.

7. I was encouraged in my “joyce-ful” pursuit of Warhol by Lacan’s writing, especially his “Lituraterre” in The Seminar of Jacques Lacan, Book XVIII: On a discourse that might not be a semblance, Cormac Gallegher, trans., unpublished; and by the “enjoy-meant” exhibited by the others who wrote after him, including, Dany Nobus, “Illiterature” in Re-inventing the Symptom, Luke Thurston, ed. (New York: Other Press, 2002), pp. 19-43; Eric Laurent, “The Purloined Letter and the Tao of the Psychoanalyst” in The Later Lacan: An Introduction, Véronique Voruz and Bogdon Wolf, ed. (Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 2007), pp. 24-52; and especially Luke Thurston, James Joyce and the Problem of Psychoanalysis. (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2004).

8. For a practical synopsis of the concept, and an abbreviated chronology of its development, see Dylan Evans, An Introductory Dictionary of Lacanian Psychoanalysis. (London and New York: Routledge, 1996), pp. 124-126.

9. Jacques Lacan, “The Purloined Letter” in Écrits, pp. 6-48.

10. Jacques Lacan, “The Purloined Letter” in Écrits, p. 21.

11. Patrick A. Smith, Andy Warhol’s Art and Films. (Ann Arbor, Michigan: UMI Research Press, 1986), p. 523.

12. Smith, Andy Warhol’s Art and Films, p. 15. In the related footnote (p. 534) Smith offers yet another anecdote relevant both to Warhol’s name change and his telephone fixation: “Andrew Warhola changed his name to ‘Warhol’ sometime in the 1950s, perhaps because of an enormous telephone bill that was in his original name…” See also a similar account in Patrick S. Smith, Warhol: Conversations About the Artist. (Ann Arbor: Michigan, UMI Research Press, 1988), p. 24.

13. Smith, Warhol: Conversations About the Artist, p.239, and ……..

14. Victor Bockris, The Life and Death of Andy Warhol. (New York: Bantam Books, 1989), p. 54; also referred to in Smith, Warhol: Conversations about the Artist, pp. 99–100.

15. Joyce closes a 1926 letter to his fiancé Nora Barnacle with this “hysterical” question. See Luke Thurston, James Joyce and the Problem of Psychoanalysis. (Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, 2004).

16. Patrick S. Smith, Warhol: Conversations about the Artist, p. 127.

17. Jacques Lacan, The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis, Jacques-Alain Miller, ed., Alan Sheridan, trans. (New York, London: W.W. Norton & Company, 1981), p. 115.

18. This is a variant spelling of Warhola and appears on Warhol’s birth certificate.

19. The inevitable phonetic similarities between English and Carpatho-Rusyn as a probable “inspiration” for and an echo throughout Warhol’s work, given the premise that it is disturbed by language, present a compelling interpretive challenge, albeit an idiosyncratic one.

20. Smith, Warhol: Conversations about the Artist, pp. 187–188.

21. Dr. Paul Robert Magocsi, The People From Nowhere: An Illustrated History of Carpatho-Rusyns. (Uzhhorod: V. Padiak Publishers, 2006).

22. Fred Lawrence Guiles, Loner at the Ball: The Life of Andy Warhol. (London: A Black Swan Book, 1990), p. 26.

23. Wayne Koestenbaum, Andy Warhol. (New York: A Lipper/Viking Book, 2001), p. 1.

24. Koestenbaum, pp. 29-31.

25. http://www.goldenageofradio.com

26. Andy Warhol, The Philosophy of Andy Warhol: From A to B and Back Again. (San Diego, New York, London: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich Publishers, 1975), p. 25.

27. This legendary clip can be heard at http://www.goldenageofradio.com.

28. This and other radio ads of the era can be heard at http://www.digitaldeliftp.com/LookAround/advertspot_campbells.html.

29. Jacques-Alain Miller, “Jacques Lacan and the Voice” in Voruz and Wolf, ed., pp. 137-146; For a philosophical slant on Lacan’s voice-object, see Mladen Dolar, A Voice and Nothing More. (The MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts and London, England, 2006).

30. Koestenbaum, p.1.

31. Guiles, pp. 53-54.

32. Milestones in this evolution are Jacques Lacan, “On A Question Prior to Any Possible Treatment of Psychosis” in Écrits, pp. 445-488; Jacques Lacan, The Seminar of Jacques Lacan, Book III: The Psychoses, 1955-1956, Jacques-Alain Miller, ed., Russell Grigg, trans. (New York, London: W.W. Norton, 1993); Jacques Lacan, The Seminar of Jacques Lacan, Book XVII: The Other Side of Psychoanalysis, 1969-1970, Jacques-Alain Miller, ed. Russell Grigg trans. (New York, London: W.W. Norton, 2007); Jacques Lacan, The Seminar of Jacques Lacan, Book XXIII: Joyce and the Sinthome, 1975-1976, Cormac Gallagher, trans., unpublished.

33. In French, there is a homophonic play between “le nom du père” and “le non du père”, the no of the father.

34. Renditions of Lacan’s formulation of Foreclosure as it relates to the Name-of-the-Father abound. I refer here to Bruce Fink, A Clinical Introduction to Lacanian Psychoanalysis: Theory and Technique. (Cambridge, Massachusetts and London, England: Harvard University Press, 1999), see the chapter “Foreclosure”, pp. 79-111; and Russell Grigg, Lacan, Language and Philosophy. (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2008), see especially the chapters “Foreclosure” and “The Father’s Function”, pp. 3–36.

35. Jacques Lacan, “Les complexes familiaux dans la formulatons de l’individu” (1938), Paris, Navarin, 1984, p.80, quoted by Herbert Wachsberger, ”From Elementary Phenomenon to the Enigmatic Experience” in Voruz and Bogdon, ed, p. 31.

36. Eric Laurent, “Three Enigmas: Meaning, Signification, Jouissance” in Voruz and Wolf, ed., p. 122.

37. Bockris, p. 25.

38. Warhol, p. 5.

39. Warhol, pp. 25-26.

40. Warhol, p. 26.

41. Smith, Warhol: Conversations about the Artist, p. 64.

42. Bockris, p. 8.

43. Bruce Fink, Lacan to the Letter: Reading Ecrits Closely. (Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 2004), p. 81.

44. Quoted in Koestenbaum, p. 39.

45. Quoted in Koestenbaum, p. 18.

46. Kynaston McShine, ed., Andy Warhol: A Retrospective. (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1989), p. 411.

47. Herbert Wachsberger, “From Elementary Phenomenon to the Enigmatic Experience” in Voruz and Wolf, ed., p. 111.

48. Jacques Lacan, “The Mirror Stage as Formative of the I Function Revealed in Psychoanalytic Experience” in Ecrits, pp. 75–81.

49. Jacques Lacan, The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis, p. 83.

50. Ellie Ragland, “The Relation Between the Voice and the Gaze” in Reading Seminar XI: Lacan’s Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis, Richard Feldstein, Bruce Fink, Marie Jaanus, eds. (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1995), pp. 187-203.

51. Jacques Lacan, The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis, p. 93-97. Lacan’s illustration here is the sardine can anecdote.

52. Andy Warhol & Jamie Wyeth: Portraits of Each Other, The Brandywine River Museum exhibition brochure, 1976.

53. Jacques Lacan, The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis, p. 103.

54. Jean-Louis Gault, “Two Statuses of the Symptom: ‘Let Us Turn to Finn Again’” in Voruz and Wolf, ed., pp. 75-76.

55. Catherine Millot…..

56. Philip Dravers, “Joyce & the Sinthome: Aiming at the Fourth Term of the Knot” in Psychoanalytical Notebooks of the London Society of the New Lacanian School, Issue 13, (March 2005), pp. 110-111.

57. Thomas Svolos, “Intercepts: Ordinary Psychosis, Omaha, 2008”, Lacanian Ink 31 (Spring 2008), pp. 185-189.

58. Rainer Crone, “Warhol’s Semiotic Practice: Signifier/Signified” in Andy Warhol: A Picture Show by the Artist: The Early Years 1942-1962, (New York: Rizzoli International Publications, Inc., 1987), p. 90.

59. Waschberger, p. 111.

60. Waschberger, p. 111.

61. For instance, the influence pysanky may have had on Warhol seems mostly to have been overlooked. The Carpatho-Rusyn folk art tradition of dying vibrantly colored Easter eggs involves a variety of painstaking repetition and reversal techniques, often, depending on the process, within a fifteen second or fifteen minute duration. For a start, and a detailed account of the various pysanky techniques, as well as other Carpatho-Ruysn cultural traditions, see Raymond M. Herbenick, Andy Warhol’s Religious and Ethnic Roots: The Carpatho-Rusyn Influence on His Art. (United Kingdom: The Edwin Mellen Press, Ltd., 1997)

62. The trajectory of Lacan’s later consequential encounter with Joyce’s writing, its precipitation of the passage from symptom to sinthome, and the related traversal of the fantasy, is traced in two outstanding essays: Véronique Voruz, “Acephalic Litter as a Phallic Letter” in Re-Inventing the Symptom: Essays on the Final Lacan, Luke Turston, ed. (New York: Other Press, 2002), pp. 111-140; and Philip Dravers, “In the Wake of Interpretation: ’The Letter! The Litter!’ or ‘Where in the Waste is the Wisdom’” in Thurston, ed., pp.141-176.

63. Jacques Lacan….

64. I refer to Lacan’s later term for Joyce, “Joyce-the-symptom”; the symptom is the true proper name particular to any subject.

65. Alenka Zupancic “When Surplus Enjoyment Meets Surplus Value” in Sic 6, Jacques Lacan and the Other Side of Psychoanalysis: Reflections on Seminar XVII, Justin Clemens and Russell Grigg, eds., (Durham & London: Duke University Press, 2006), pp. 155-178.

66. Svolos, p. 189.

Robert Buck © 2009

Download

.png)