What Lacan Knew About Women: The Miami Symposium

On the occasion of the release of the journal” Culture/Clinic”, University of Minnesota Press

Eden Rock Hotel, Miami, FL | June 1 & 2, 2013

Synopsis

In David Lynch’s 2006 film Inland Empire, an actress wins the lead role in film about a love affair. The plot of this film-within-a-film is echoed in the life of the actress when she and her male co-star have a clandestine affair. During the first rehearsal, it’s revealed that the script is cursed by a Polish folk tale and that the two leads in an earlier production of the film, titled “47”, were murdered. This disturbing news casts a shadow across the current production, and Lynch’s film as a whole.

We first see the main character, Nikki Grace, played by Laura Dern, when she's visited by a new neighbor, a strange Polish woman. The older woman distresses Nikki by telling her a parable about the birth of evil in the world, and by prophesizing that she will get the role she’s hoping for in the film, “On High In Blue Tomorrows”, but that a “brutal fucking murder” will occur.

The parable has two variations: the story of a little boy who, when stepping from his door into the world, casts a reflection, and gives birth to evil; and the story of a little girl who, “as if half-born”, is lost in the marketplace. Yet the Polish woman suggests that Nikki knows that the way to the palace is not through the market place, but via the back alleys behind it.

The clairvoyant woman also introduces the first of many discontinuities in the film, as it charts a labyrinth of kaleidoscopic narratives. The first disruption occurs when the neighbor woman directs Nikki to look across the room, where she sees herself with friends, days later, taking a phone call with news that the coveted role of Susan Blue is indeed hers.

So begins Nikki’s odyssey, one that is haunted by the ominous parable. Lynch’s central narrative device is the film-within-a-film, a Hollywood convention. He uses it to exploit the division produced in Nikki as an effect of the strange woman’s parable. During the production of the film, Nikki Grace as Susan Blue travels through a maze of alternate dimensions represented in the film as half-built sets, alleyways, corridors, and dark passageways. Nikki's odyssey appears to end with Susan’s death in the film-within-the-film, but when she wanders past the camera and off the set, she breaches the formerly established narrative framework. She's now able to navigate a warren of spaces that had been previously disconnected, and commits the foretold murder. Ultimately, she finds herself back in the room where she began, and confronts yet another incarnation of her self.

Parable

The parable introduces the first moment of Nikki's subjective division. This split corresponds with the way the character is described by the Polish woman, as a girl “half-born”, lost in the marketplace, pretending to be unaware of her circumstances – qualities of the quintessential hysteric pantomime. Yet while Nikki/Susan will spend the rest of the film ostensibly lost, wandering the back alleys of the sound stage, her story is not that of the classic hysteric. She is a woman who gradually uncovers another kind of knowledge. It is along this trajectory that the effects of the parable-signifier will slowly unravel throughout the film.

The story of Inland Empire has to do with a woman's affair and a murder. The suggestion of an affair with her co-star is imposed on her from multiple sources – including a TV talk show host, backstage gossip, the script she’s at work on – until it’s no longer a stereotype of the Other’s discourse. It becomes her own story, and she plays the part. The woman who is “half born” is the woman who does not exist, but must always come to be. Indeed, Nikki works with the veils of femininity that she wears, but they also work her: wife, adulterer, Hollywood actress, mother, madwoman, femme fatal, “bad ass” (the woman with nothing left to lose).

A second moment of subjective division occurs when Nikki confuses her real life affair with the plot of the script. She breaks from shooting a scene to exclaim, “Damn, that sounds like dialogue from our script!” The director yells “cut” and impatiently asks what’s going on, as Lynch’s camera pulls back to reveal the camera of the film-within-the-film trained on Nikki. But she’s right, the dialogue is from their script! This collapse of outside and in, character and self, perplexes her. Henceforth she is unable to hold the same co-ordinates of reality. The story of the character begins to blur with the narrative of the film. The old wive's curse has begun to take effect at the level of Nikki’s body. The signifier of the curse creates a moment of subjective confusion, accompanied by anguish and jouissance. Yet it is the same parable that Nikki will continually recompose throughout the film in order to forge a knowledge with which to deal with her jouissance.

'You on high now, love'

If the film Inland Empire has a Name-of-the-Father it would be “Hollywood”. The name of Nikki’s character, Susan Blue, shares a signifier with of title of the script, “On High In Blue Tomorrows”. Inland Empire foils expectations by warping the traditional male odyssey narrative. The conclusion of the film-within-the-film is only one threshold of “The End”. A beyond appears within the film. Instead of the classic male hero’s odyssey –– a journey of the one as exception (such as cowboy, warrior, detective) –– Nikki’s story is multi-dimensional and situated at a boundless horizon. It’s as if the only way narrative filmmaking can approach the story of a woman is through half-truths, fragments of knowledge, and multiple versions of The Woman.

We witness something that gradually exceeds and dismantles the narrative framework. The signifier “Hollywood” we start with no longer holds by the end, and the resolution we might have arrived at under phallic sense fails. For the male characters in Lynch’s film, the curse on the previous production “47” may simply be an unsettling story, but for Nikki it is the haunting realization of the old wives tale, one felt at the level of her body.

At one point, Nikki winds up at the corner of Hollywood and Vine, where she’s stabbed by a shabby-looking woman, recognizable as the wife of her co-star lover in the film. As she lies bleeding among several homeless people, one of them offers her solace by naively reformulating the title of the film, “On High In Blue Tomorrows”, recomposing the signifiers as “You’re just dying that’s all. No more blue tomorrows, you on high now, love.” The reconfiguration of these master signifiers serves to dissolve a certain identification for Nikki, allowing her to better handle her suffering for the remainder of the film.

By re-ordering these signifiers, and destabilizing “Hollywood” as a Name-of-the-Father, merely one of many master signifiers that operate in the film, Lynch is able to redirect “The End” of the film from a limit to a beyond. His camera zooms out to reveal the camera of the film-within-the-film recoiling from Nikki as she lies dying. This horrifying moment echoes the earlier one in which Nikki confuses her life with Susan Blue’s. We sense that while she dies under the surveillance of the camera, it is the gaze as void that she’s confronted with beyond the plane of the lens. Yet it is precisely in the wake of this confrontation, and the reformulation of the signifiers, that Nikki exits the scene. She traverses the frame of the film-within-the-film and wanders, vacant yet compelled, off the soundstage. Ultimately, her passage charts the dissolution of the Other's consistency. This is another way to understand Inland Empire, as a film of the era of the Other That Doesn’t Exist. If one aim of psychoanalysis is to touch the real, then it’s not surprising that Lacan's discourse would converge with what Lynch brings into focus: the traversal of the narrative frame as an experience of the void, as horror.

Sound Stage

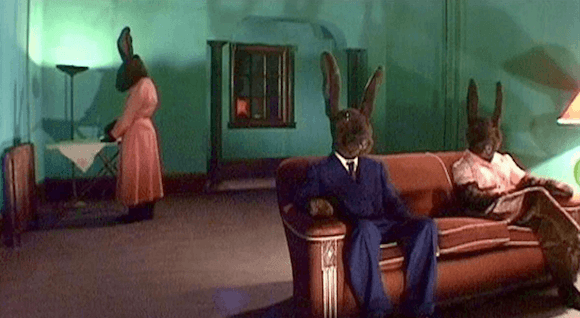

The viewer also experiences a disorientation akin to Nikki's. Lynch’s central figure for this perplexity is a theatrical diorama with a trio of human rabbit figures. This scene, which bookends the film, establishes “set” and “stage” as imaginary devices to convey her perplexity. The film was shot entirely on digital video, which adds to the malleability of narrative formalities.

At the symbolic level, the stage can be understood as the locus of the Other. The sets of the movie become a topological version of Nikki’s subjective position. This topology is Mobian. It is the “other scene” literally, the back-lot, in which her subjective destitution unfolds. One quality that distinguishes Inland Empire from other contemporary films is that there is no identifiable “outside”, either to the film-within-the-film, or at the level of the signifier. There’s no meta-language that would typify a traditional narrative according to phallic logic.

The consummate way to understand the set/stage device is as semblant. Lynch re-works “Hollywood” as the semblant par excellence. But how does Nikki Grace contend with the semblant? She is unraveled by the confusion between the woman she is and the woman she plays. In spite of her perplexity, the combined “role” she’s given by the others – the old woman, talk show host, and the director, to name only three – is to live through the mortifying effects of jouissance and the feminine masquerade. In the end, Nikki takes the stage again. Her newfound knowledge of the semblant purifies the set/stage to an empty theater without spectators and without actors.

“This is the kind of shit I’m talkin’ about”

One effect of Nikki's ability to endure instances of subjective division is a transformation in her relationship to speech. This is exemplified by a scene in a dilapidated room, wherein a man listens to her recount violent episodes. There is now grit and symbolic economy in her speech in contradiction to earlier scenes, like the one in which her male co-star tells her that she “talks too much” while they’re having sex. As she speaks now, whether the man sitting across from her is listening or not becomes irrelevant for her. Here the figure of the Other is de-completed. This is the scene in which Nikki realizes she’s a character in her own story, and assumes her status as “actor”, cognizant of its quality as a semblant.

Rather than being cast in a role assigned by the Other, for the first time she’s able to tell a love story, one of dissolution and ravage. It’s through her reorientation of the signifiers – for instance, screwdriver, light bulb, an unpaid bill, after midnight, room 47 – that she is able to re-graft her new relationship to jouissance. This scene transports her to the intersection of Hollywood and Vine, where prior to her death in the film-within-in-the-film, she shouts to a group of prostitutes, “I’m a whore! Where am I? I’m afraid.” These lines are delivered with derision and contempt in contrast to the uncertainty she experienced previously when confronted by these same signifiers via injunctions from the old woman, the film director, her husband, and her co-star.

Towards the end of the film, Nikki enacts the 'brutal fucking murder' foretold by the neighbor woman when she shoots a terrifying figure she confronts in a hallway: her own distorted face, a bleeding mouth, superimposed on a strange a man. The dead man becomes a grotesque representation for her encounter with the non-sexual rapport. It’s no coincidence that the murder happens outside the door of hotel room number 47 – the title of the cursed film and, it turns out, the site of the theatrical rabbit scene. Here Nikki confronts the hole sexuality tears in knowledge, one that she has circled around via the many manifestations of the 'love affair' throughout the film.

A Hole in Horror

A recurring feature of the film is a “greek chorus” of young girls, which comprise a series, one that Nikki comes to realize she is not an exception to, but instead a singularity. They signal the way to a knowledge of how to contend with the non-sexual rapport, a new knowledge that Nikki comes to work with by the end of the film. These young girls, evincing a sense of “know how”, instruct Nikki to burn a hole in silk lingerie. Behind the hole is another veil of silk.

Lynch creates the temporal and spatial structure of the film not unlike the unconscious, and Nikki is never able to apprehend herself as the consciousness of the film. Lynch is dedicated to the unconscious, but what we discover with Inland Empire is distinct from the transferential unconscious. It is the enigmatic digital viscera of Inland Empire that gives texture to the unconscious as real. Questions without answers, perplexity, holes in knowledge, no solutions, a cinema that doesn’t abide by phallic limits – allow us to experience what’s troubling about horror, a hole in horror itself. In one sense, Inland Empire provides a “classic” Hollywood account of the story of the horror of castration. But Lynch goes further, and renders that which is beyond the trauma of castration. While it is impossible to inscribe the sexual rapport that does not exist – although Hollywood endlessly attempts to do just this: to script that which does not stop not being written – it is through the story of a woman and the logic of the not-all that Lynch is able to evoke it. He exploits the semblants of our hypermodern era to work otherwise, towards the horizon of the real of the non-sexual rapport.

Robert Buck and Cyrus Saint Amand Poliakoff © 2013

Download

.png)