Whitney Museum of American Art

April 2, 2016 – February 12, 2017

http://whitney.org/WhitneyStories/RobertBuckOnGeorgiaOKeeffe

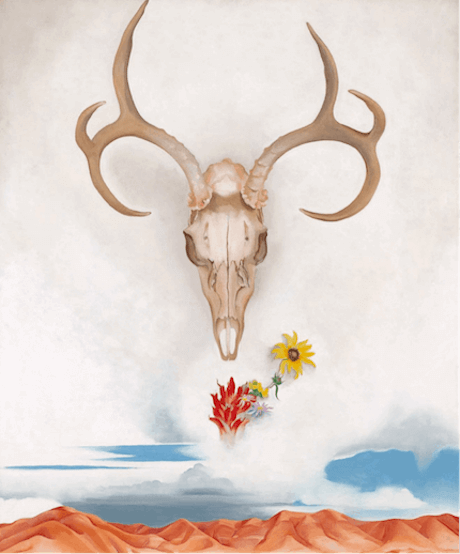

In coming upon “Summer Days”, we are confronted to an object, skull, remainder. And to silence. I can 'hear' the high noon stillness of the desert, sun in my eyes, skull as afterimage, mirage. Yet I’m confounded. Shouldn’t this thing, bone, sun-bleached and sanded, be found at my feet not elevated above me floating, noble and majestic? Cipher. By what fantasmatic turn, magical, shamanistic, alchemical, does this litter, the remains of a predacious and violent event – not the act of a hunter, who would have taken the antlers as trophy – weathered by time, come to embody something sacred? Detritus as deity, sacrosanct, holy. The flowers and the approaching storm on the horizon provide a clue. It’s a still life, vantias, memento mori. But there’s something else, ineffable yet hidden in plain sight. The anamorphic skull in Holbein’s “The Ambassadors” comes to mind. Although O’Keeffe’s skull is not mistaken for a stain on a carpet, it’s no less compelling as a shape in the clouds, glyph, divination in the bone, traveling in the opposite direction, not a fallen object but an elevated one. It seizes me, looks back at me.

All artwork is organized around a hole, incorporates and betrays it. In “Summer Days” this is the emptiness of the desert in the frame, the divots in the skull, the sockets without eyes. O’Keeffe explicitly raises an object to the dignity of the Thing, an object forever lost that lies beyond or outside representation. In “Summer Days” the primordial existence of that Thing is uncannily implied. The deer skull resonates as something imagined yet real––remains, relic, artifact, which O’Keeffe salvaged I imagine while out combing the desert. Better, it came across her. She was seen, riveted. She memorialized it, as talisman, witness, portrait? With a contour of the sublime, Real. She explicitly renders creation ex nihilo, creating a hole so to screen or embroider it. The desert is depicted as an emptiness to be filled. This is a central paradox: a hole wouldn't exist if the painting wasn’t created in order to plug it. What is a hole if nothing surrounds it?

“Summer Days” is less a portrait than a portrayal, an index of the transfiguration of the remainder into an icon or sign. Time implied in the painting by the weathered bone and the time of its making. Sublimation. I’ve been making a series of paintings entitled “The Letter! The Litter!”, canvases that are my embellished transcriptions of scraps of writing I find on the street, discarded or lost remainders of a correspondence, diary, or publication – lives. Like O’Keeffe did, I spend time in the West, in the low and austere desert of far West Texas, along the border with Mexico. I search there too for traces, parts, bits and pieces.

My mother was an artist, a Sunday painter. She was adventurous, but as a woman in the era of “Mad Men”, she didn’t travel often or far. However, as a young woman she sojourned in New Mexico. Starting in 2002, in the wake of 9/11, I began taking exploratory trips out West, choosing towns on the map that called to me by their name. One of those place-names was “Truth or Consequences”, NM. From there I made my way north to Taos, where my mother had gone, O’Keeffe too. I was aware of O’Keeffe’s paintings as a teenager. They were exotic, yet because they were omnipresent, stereotype and cliché. They still can be, which is in part why I wanted to address her work. I encountered “Summer Days” in the museum in a manner analogous to O’Keeffe’s coming across a skeleton on the desert floor. “Summer Days” is an allegory for this transfiguration of the skull to Thing to art. Littered by the artist’s body and then salvaged by the museum. O’Keeffe’s work circulated in the age of mechanical reproduction, which is how I originally encountered it. But what about it, or any work, in the digital age of sliding, scanning, swiping? In the ocean of images it’s the 'something else', singular, that beckons each of us individually, an object or image that disrupts, akin to the punctum that smote Roland Barthes when finding in a photograph the “air” of his own Mother.

I’ve lately been interested in the Feast of the Transfiguration of Christ. Although I was raised Catholic, I was unaware of this holiday, one which I can appreciate not only spiritually but artistically. Art is nothing if not an act of transfiguration of the object. Transfiguration is exemplified by “Summer Days”, the skull forming an axis between heaven and earth, radiating a kind of fantasmatic light, as we bear witness to it. The paradox and poignancy depicted by the painting is that to love or venerate a thing is also to kill it, to mutilate it, to extract from it something more than it is. To go beyond it.

Only after I chose to respond to “Summer Days” did I glimpse through it the act of changing my father’s name by a single letter from Beck to Buck, a maneuver that queries the status of the Name-of-the-Father precisely as an artifact, left-over, hand-me-down. The Name-of-the-Father changed irrevocably in the 20th Century, causing each of us to invent our own, knowingly, explicitly, or not. (Caitlyn Jenner would be a recent and well-known example.) I did so literally, with a simple exchange of vowels, as a means to call attention to this evolution. Buck: stag, son, cash, dislodge.

O’Keeffe venerates the buck not only as a hunter might but as an artist. This is how I came to understand “Summer Days”, among many other things, as a kind of notary for the name I made for myself, through art, the only discourse in which it matters and creates effects. Not long ago, I came across a quote from French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan, “One can do without the Name-of-the-Father on condition one makes use of it.”

Robert Buck © 2016

Download

.png)