Clinical Study Days 6 Conference of the Lacanian Compass

New York, NY | February 24 – 26, 2012

"The Readymade and the Act" by Tom Ratekin "The Readymade and the Act" by Tom Ratekin

“The Readymade and the Act” by Tom Ratekin – A Response

I want to thank Tom for his paper, which invites us to reconsider a founding moment in the history of modern art via the psychoanalytic act.

I can pick up the gauntlet only by asking questions that seem essential to advancing this considerable proposition, but untangling the knot that binds artist, audience, object and other is for me daunting. So the best I can do here is to offer a few incentives beyond what Tom has proposed.

I’d like to look closer at what led Duchamp to carryout his consequential maneuver.

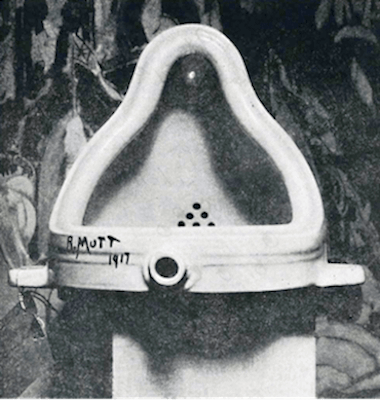

And to bring on-screen what is often left off of it, the name, an invented name, “R. Mutt”.

How to account for the salient concepts that would truly distinguish an act in art from one in psychoanalysis? What I have yet to satisfactorily work-through: how to locate the transference – that is to say, the Subject Supposed to Know – and can an act in art be achieved without it; what of the effects, and the knew knowledge that results; what of the status of the Other; or the drive; and most important to art the object, which, as Tom mentioned, was in the present case lost from the start.

Indeed, the object itself was never exhibited, and the signed original disappeared. So, crucially, it’s the lost object, cause of desire, that Duchamp presented us with in 1917, around which the drive circulated, still circulates, albeit since mitigated with the production of eight facsimiles.

To provide some background, the 1917 Independents Exhibition was open to any artist willing to register for a six-dollar fee and it was Duchamp’s idea that the works should be installed alphabetically by surname. His gambit as a challenge to the “no jury” policy of the panel was that R. Mutt’s urinal would be refused. An added twist is that Duchamp himself was a member of the jury and that other members, namely Walter Arensburg and Joseph Stella, who had accompanied Duchamp on his shopping quest for the urinal, were also in on the joke.

In his essay “Blame It On New York” – which he gave at the start of Clinical Study Days 4, in October 2009 – Pierre-Gilles Gueguen effectively sets Duchamp’s calculated maneuver of 1917 against the refusal of his “Nude Descending A Staircase” from the 1912 Salon of Independents in Paris. He notes, with reference to Duchamp biographers, that the refusal of this painting, a major modernist work, had a traumatic effect on the young artist. As Pierre Gilles writes further: “For the artist, the art object is a unique object that stands out against a background of what we shall call ‘trauma’ to use a generic term. It is particularly clear in the case of Duchamp’s ready-mades. To face up to a threatening hole that is real, the artist ‘invents’ an object that keeps up a particular relationship with the body.”

Can an Act in the psychoanalytic sense be detected here? Is it the trauma of being refused in 1912 that Duchamp re-enacts, or re-signifies, with the refusal of the urinal five years later? Was the consistency of the Other shaken for Duchamp with the first refusal? If so, was the refusal of 1912 an Act? Did the act Duchamp carryout later generate a new Other as Fabian said yesterday? Did it re-establish a social link? How can we account for the act in relation to cultural works? How is it inflected differently in the clinic? Would each one be singular? Does “Lacan with Joyce” show the way, even though it’s not writing but the object that concerns us with Duchamp?

And after this morning’s session, some further thoughts: Answering the question who performs the act becomes especially mecuriall here. Was the refusal the act? Was the transference to the “non jury panel”? And to borrow Pam’s beautiful term, was George Bellows, apparently the loudest voice against Mutt’s inclusion, the “analyst curator”?

An additional quote from Pierre-Gilles’ essay tellingly locates Duchamp’s act, his “Fountain”, as the urinal was titled, as an end and a beginning. “There would thus be the ‘uplifting’ sublimation, from the time of Freud, and the ‘downward’ sublimation, the sublimation of the hypermodern era which gladly presents regular objects or objects of disgust as art objects”.

About the body and jouissance, it may also be worth considering the metonymical relationship a urinal has to the body. It was therefore perhaps no coincidence that it was this particular readymade – there had been two before it, “The Bicycle Wheel” and “The Bottle Rack” – that took hold. From Calvin Tompkins’ biography, “Not one of the accounts published at the time identified the controversial object as a urinal – decorum required that it be referred to as a “’bathroom fixture’”.

As we know, language in Duchamp’s art was central, and writing had a significant part to play with the urinal, beyond the inscription of the self-nomination and date on the object itself. But here we find writing after the fact, words that would in away direct the historical significance of the object’s refusal. Duchamp wrote, again under the name “R. Mutt”, an editorial to a “little magazine, titled ‘The Blind Man’”. It was started by Duchamp and two other organizers of the Independents Exhibition, and came out two months after the infamous act.

“THE RICHARD MUTT CASE” from Calvin Tompkin’s biography “Duchamp”, Page 185:

They say any artist paying six dollars may exhibit.

Mr. Richard Mutt sent in a fountain. Without discussion this article disappeared and was never exhibited.

What were the grounds for refusing Mr. Mutt’s fountain: –

1. Some contended it was immoral, vulgar.

2. Others, it was plagarism, a plain piece of plumbing.

Now Mr. Mutt’s fountain is not immoral, that is absurd, no more than a bathtub is immoral. It is a fixture that you see every day in a plumbers’ show window.

Whether Mr. Mutt with his own hands made the fountain or not has no importance. He CHOSE it. He took an ordinary article of life, placed it so that its useful significance disappeared under the new title and point of view – created a new thought for that object.

As for plumbing, that is absurd. The only works of art America has given are her plumbing and her bridges.

A bit about “R. Mutt”: the alias was a allegedly a play on Mott; the porcelain urinal had been purchased at J.L. Mott Iron Works, a manufacturer of plumbing equipment on Fifth Avenue, but it also referred to the comic strip “Mutt and Jeff”; and the letter R, stood for Richard, which in French slang chimes as “moneybags”.

Before concluding, some things to think more about:

Is there some worth in likening Duchamp’s ready-mades to Joyce’s equivocations, those snippets of conversations he would hear, repeat endlessly to himself, and insert in his writing? Again Duchamp from his editorial: “He chose it. He took an ordinary article of life, placed it so that its useful significance disappeared under the new title and point of view – created a new thought for that object.” Could they too be considered as elementary phenomena?

Cannot Duchamp’s description of having an appointment with a readymade object – a contingency which he cannily called the “ready found” – and the delay he so famously articulated as THE characteristic of what is genuinely new, be ciphered as the logical times of Lacan: the instant of seeing; the time for understanding; and the moment of conclusion?

Robert Buck © 2012

Download

.png)