“That perhaps is what style comes to: the preponderance of Throwaway over Takeaway.”

—D.A. Miller, “Lost in the Detail,” Chuo University, Tokyo, Japan, October 2017

“There’s no such thing as Woman, Woman with a capital W indicating the universal.

There’s no such thing as Woman because, in her essence...she is not-all [pas-toute].”

—Jacques Lacan, The Seminar of Jacques Lacan, Book XX, Encore: On Feminine Sexuality,

The Limits of Love and Knowledge

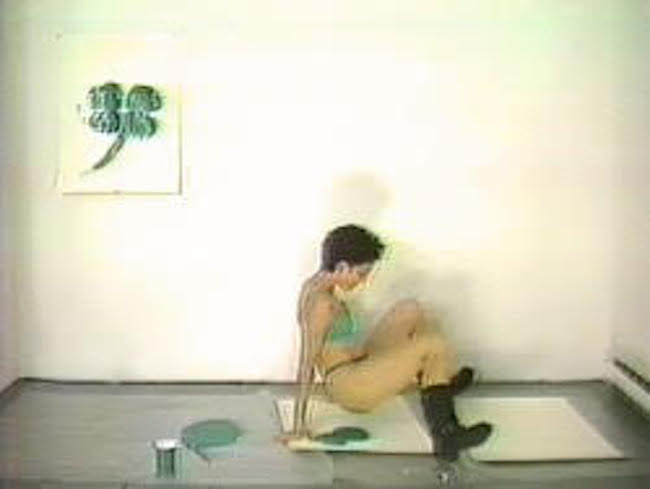

Fig. 1: Cheryl Donegan, Body Type, 1993. Video, color, sound, 11:17 min.

Courtesy the artist

Fig. 2: Cheryl Donegan, Kiss My Royal Irish Ass (K.M.R.I.A.), 1993. Video, color, sound, 5:47 min.Courtesy the artist and Electronic Arts Intermix (EAI), New York

ADAM’S RIB

What happenstance, what happiness, to have discovered in the homophonic

equivocation of the syllables that drop from the dissection of an artist’s name—

shear, all, done, again—the constitutive and heretical parts of her practisse!

1 I had to look, and look again, at her more than thirty video works in order to spot the clues covered in clear sight, on the skin as it were, like “Adam’s” rib or thigh “master,” two of the puns that riddle her body in Body Type (1993; Fig. 1). By doing so, I was able to divine in the shards of her name her know-how to reuse it; to bypass the Name of the Father as a woman who renounces the repetitive citations of

metaphor for the endless desires of metonymy. 2

Donegan’s work was forged in nineties art-making ideologies, notably identity politics and the valuation of video art as white-cube commodity. 3 But more importantly, her artistic development spans a seismic shift in civilization, the unprecedented collusion of capitalism and science, and the consequential ascendance of consumer technology to the social apex. Donegan’s video works not only traverse these market, techno-scientific developments, but also tick with their time, each installment of her ongoing series signaling our way. 4

Pursuing her works chronologically distills their logical and atemporal coordinates, that is, what transpires “inherently.” 5 Her initial aim was to have it all, yet each exploit left a remainder—loaf heel, banana bit, spilled milk, paint-print on a studio chair, doubt. It is with this surplus, impossible to anticipate or quantify, that Donegan will orient her singular know-how to proceed. At the crux of her artistic operation is the body, as an enjoying substance; in her case as cavity, vacuole, or sack—My Plastic Bag. 6

K.M.R.I.A. / I MARK

Donegan’s first scission was the bite, which she uses in Gag (1991; page 248)—the first

of her single-action “turn it on, turn it off” works.7 Her hands may be bound, but

the gag is on us, for she succeeds in demonstrating the impossible, to eat an entire

baguette inserted upright between her legs. Make no metaphorical mistake; the

loaf is not a cock but a clock. With futility as her aim, herewith, Donegan privileges

logical time over real time. Her prank is less Coney Island stunt than practical

performance art—the art-historical designation for what she recurrently disrobes

as drag. With the 1993 video limerick Kiss My Royal Irish Ass (K.M.R.I.A.) (Fig. 2),

Donegan embarks on her quest to merge mark- and moving image–making. In

K.M.R.I.A., she uses her body as a template for printmaking, a transfer process

that will become one of her primary techniques. In Head (1993; page 267), she uses it

to suck, siphon, and spit milk—regurgitate, recycle, relay.

Head is a single-take escapade, in which Donegan synchronizes or “cuts” her actions to a pop tune. 8 While her feeding and milking of the object may be timed to the music, logical time, again, outdoes duration, as she exits the frame before the song is done. Milk remains in the plastic bottle, leaking from its punctured hole, hard to swallow. Made in the heyday of music video kinestasis, Head dissented in its static, single take. That Head brought to a head the explicit aims of Donegan’s earlier exploits isn’t enough to explain its popularity. Nor does its DIY use of a then newly available consumer-based camcorder. What then, a quarter-century ago, made Head a hit? It’s more than while watching we consume her consumption, like the living dead devouring living life.

Ahead of her time, in a hypermodern act of consecration, Donegan devised a pleasure “device.” Input. Output. It could have been any detergent bottle, degenerated, stripped of its label: Gain, All, Cheer, XTRA. Exchange value condescends to use value, taken to its logical libidinal surplus XTRA extreme. Explicitly raising the object to the dignity of the Thing, Donegan makes a spectacle of sublimation: “This Thing, all forms of which created by man belong to the sphere of sublimation, this Thing will always be represented by emptiness, precisely because it cannot be represented by anything else—or, more exactly, because it can only be represented by something else. But in every form of sublimation, emptiness is determinative.”9 But as Head happened at the dawning of the iSpace10 age—each one-all-alone with their particular combinatory mode of enjoyment: oral, anal, invocatory, scopic, drive objects11—Donegan’s bottle also resembles a lathouse. This is the designation Lacan gave in 1970 to mass-produced objects, specifically objects of entertainment, a neologism that includes ventouse, the French for suction cup, and Ousia, which, in Aristotle, signifies both substance and being.12 In the twenty-first century, when our hand-held devices insist that nothing is prohibited, and everything is perpetually permitted, Head also anticipated the prevalence of pornography in everyday life.13

In Make Dream (1993; page 274), Donegan struggles to sling paint from a canister, hung from her waist, against a plastic sheet. But to signal it’s a waking- dream, Donegan, for subtle but decisive effect, reshoots her Ab-Ex painter pantomime off a monitor screen. Her painting spree, splattered between the transparent tarp and the TV screen, appears vitrified. We apperceive the screen as lens, viewfinder, or vitrine, and in the meta-materiality of the glass, the gaze and Donegan’s attention to it. Sight and gaze do not correspond. “The gaze I encounter is, not a seen gaze, but a gaze imagined by me in the field of the Other.”14 Yet, while an artist solicits the gaze, she simultaneously veils or buffers it, which explains the dreamy picture quality of the work. Meanwhile, the pointlessness of attempting an artwork devolves pointedly as all work. Again, Donegan succeeds otherwise, by throwing her body at “it”—backdrop, performance, Pollack, phallus. By the end, spent, as the camera pulls focus, she appears “wasted,” as a blot or smudge.

In Body Type, life between Symbolic and actual death is burlesqued. Donegan presents her body as a palimpsest, as already having been fleshed-out by the signifier. She denudes the body’s dissection through language by writing words on specific parts to produce a pun, e.g., “tube” on her breast or “talk” on her back. And so obvious as to be overlooked15 is Donegan’s doing this in reverse for the words and letters to be read left to right by the lens. Body Type is a taxonomy of body parts as witticisms refracted by a mirror. That demands are whispered to Donegan by a woman off-screen—directions on how to position her inscribed body in relation to the camera—only heightens the “between two deaths”16 aspect of the piece. The body’s dismemberment by signifiers recurs with Donegan’s later sewing-pattern scrolls and tracksuit resist paintings—the body apportioned, sheared, arrayed.

Fig. 3: Cheryl Donegan, Practisse, 1994. Video, color, sound, 6:40 min. Courtesy the artist and Electronic Arts Intermix (EAI), New York

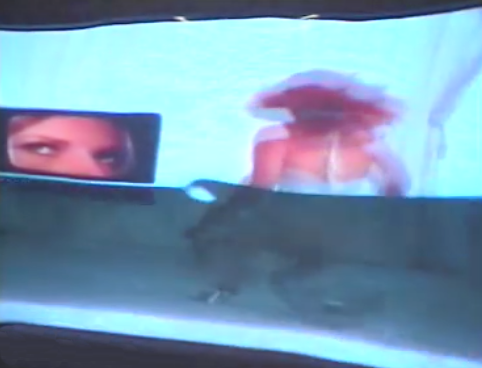

Fig. 4: Cheryl Donegan, Artists + Models, 1998. Video, black-and-white, sound, 4:43 min. Courtesy the artist and

Electronic Arts Intermix (EAI), New York

Most of the early works are deliberately staged exercises in futility. Yet, some indication of the impossible aspect abides throughout the progression of Donegan’s project; an “art coefficient”17 that betrays the work’s logical facet. To consider this dimension is to first discover that Donegan performs performance. She utilizes it. She works with the semblants of performance as a means to record an action, one that will become, for a period, almost exclusively painting. Yet, staged as contingent on the conditions of the video recording, the act of painting belies another cause, a “beyond,” deriving off- or in-screen. A seamless backdrop, pellucid pane, or plastic bag are among Donegan’s surrogate surfaces for painting— sprayed, stamped, spilled, or spat on. Call it “Action!” Painting. Outlier, harbinger, heretic, Donegan is slave to two masters. While making a mark, she makes a video, both in real time and corporeal.The body, as implement, substrate, template, and palimpsest, will persist throughout her time-based works.

EVERYTELLING HAS A TAILING AND THAT’S THE HE AND THE SHE OF IT

The planes of paper, Plexiglas, camera lens, and TV screen collapse in Clarity (1993;

page 262). Here, Donegan’s concern with surface fully surfaces. Through the

transpositions she enacts between a face-painted cellophane shroud, transparent

layer, and monitor screen, she establishes an interstice between painting and

video—the two behaving more like membranes than mediums. Analogous to

performer, screen, and camera, she now effectively posits painter, canvas (or in this

case paper), and transfer. The magical moment in Clarity comes when, having

departed the scene, Donegan freezes the frame, and the indelible stain of her mask

impression, eerily left floating aloft, fuses the layers that had mediated the visual

field: paper, Plexiglas, lens, and screen. As a collateral effect of her maneuver

to substantiate a realm between painting and video, masquerade and veil obtain

their imaginary “consistency.”

With its limpid layers and planes, and painterly transcriptions and transpositions, Practisse (1994; Fig. 3) is a reboot of Clarity that reiterates painting as contingent upon the conditions of the pro-filmic event. However, Donegan redoubles them—and thus the mark-making possibilities they present her with—by using the monitor screen as a painterly surface. Through Donegan’s mutable and multifaceted self-portrayals, the enigma of the woman is directly introduced. The audio accompaniment is a 1929 recording of James Joyce reading the “Anna Livia Plurabelle” section of Finnegans Wake, “A chattering dialogue between two washer women who as night falls become a tree and a stone,” or a glove (Joyce’s ecstatic metaphor for his partner Nora Barnacle).18

Craft: a tape by Cheryl D. (1994; page 277) is Donegan’s throwback to the music clip. The bite is reintroduced as she nibbles out emoji-like symbols—happy face, star, heart, bunny—from the makings of a Kraft cheese sandwich. She then inserts her cutouts into absurd real-life situations, which are, in turn, tessellated by an in-camera effects-generator. While the signifier “tape” in the title denotes the material substrate for video, it also implies craft-making. Yet, it is the nomination “Cheryl D.” that betrays what is otherwise being created in crafting the tape: a woman. Here, Donegan explicitly seduces, wearing lipstick, nail polish, and eye shadow, periodically flashing her baby-blues for the camera. The propulsive, male, punk-rock soundtrack quickens the sexual pulse. Drag, persona, masquerade, doll—Donegan proposes that both videotape and woman are substrates, mediums by which creations are crafted.

With scenes of restraint, confinement, futility, and happenstance, Rehearsal (1994; page 285) restages mark-making qua video-making, but ciphers the woman as contingent too, imminent, probable, pending. She exceeds the frame— painting, monitor, and mirror—and thus knows how to handle it otherwise. Dramatically shorn of her hair, Donegan, with characteristic wit, paintbrushes “hair” on her head in one scene, and uses it as a paintbrush in another. In a later scene, crawling naked beneath a transparent sheet that tents her and a television set, she paints what appears on the TV screen—images of boxers from a work by Allen Ruppersberg—along the inside surface of the plastic tarp. The distorted, flaccid faces read less as portraits than portrayals of futility and impotence, and accumulate as an inky mess that ultimately blots out Donegan. She’s done it again! Painting and performance are rendered as false choices, which directs attention elsewhere, to the “obscene” of what is seen, a woman and her body.

PLUS, NOT AND

Donegan’s utilization of her body as a medium is also a means of her enjoying it.

This jouissance takes on its full feminine, nonuniversal, and singular dimension

in several works in which other representations of the woman, including Donegan

herself as mother, enter the frame. Brigitte Bardot appears in Line (1996; page 291),

a work that straddles two art-historical supports for Donegan’s liminal position as

painter and video maker: Barnett Newman’s zip paintings and Jean-Luc Godard’s

Le Mépris (1963). Bardot is explicitly woman, sex symbol, and Donegan’s mimicry of

her is done as a skimpy semblance in a blond wig and bath towel. When Donegan

portrays the Michel Piccoli character, it’s in fits of futility and vexation—failed.

A surplus-jouissance is explicit in the unremitting and exuberant title Alive!Artist!Model!Pleasure! (1998/2015; page 303), in which life, artist, model (woman as represented by Donegan), and enjoyment are indivisible. Donegan fulfills her exclamatory incitement by directing a nutty parody of the comedy duo Jerry Lewis and Dean Martin’s Artists and Models musical number. While her particolored, musical theater, art-class antic literalizes the lyric, “So to each creator an imitator, who daubs and dabbles with the brushes,” her madcap rendition also lampoons the nostalgic, phallic sexuation of the 1955 Frank Tashlin film: “To the guys that draw... [and] To every girl that poses...”

Why not paint or perform exclusively? Why take time to record the work in real time? What does the simultaneity of video playback allow Donegan to achieve that she couldn’t otherwise, and thereby make it indispensable to her know-how, style, or savoir faire? Why, in other words, is it central to her operation as a painter? What does the video medium offer Donegan if it’s not that she can be both artist and model? “From the outset, we see, in the dialectic of the eye and the gaze, that there is no coincidence, but on the contrary, a lure.”19 Are her performances as painter, and her paintings as performance, not precisely her fabrication of a lure? Her 1998 work Artists + Models (Fig. 4) isn’t titled “artists and models,” but “artists plus models,” not apart but together.20 The dual identification is facilitated by the monitor-mirror—frame within a frame, on- and off-screen, before and behind the camera, inner- and outer-space, intimacy and extimacy.21 What does Donegan’s equation add up to? It certainly isn’t the “model artist”! In Artists + Models, she handicaps herself in a garbage bag, able to only crudely paint with the brush in her mouth. In the end, the camera finds her enclosed in the black plastic bag, stamp-patterned with a white fingerprint icon—denoting identity and identifications both—curbside with the trash. Donegan’s artistic gambit is to continually extract what cannot be accounted for.

The aptly titled trilogy The Janice Tapes (2000), heard as “Janus,” recalling earlier pieces while foretelling new ones, is the first work Donegan edited herself, using Final Cut Pro.22 In all three videos, Donegan is pregnant. It is impossible to imagine the exuberance and audacity of the ternary work separate from the signifier “reproduction”—reproduction, and all of its associations, is germane to the work. However thin, the realm between painting and video is now fully established by Donegan, and she inhabits it jubilantly. The frames of painting, performance, screen, and studio are now interchangeable, and she shuffles them freely. The plastic bottle object of Head indexes this playfulness. After reappearing in Line as a proto- camera, it’s reprised in the trilogy: in Lieder (page 323) as a headdress that discharges milk; and in Whoa Whoa Studio (for Courbet) (page 334) and Cellardoor (page 313) as a Cyclops-like protruding eye, alternately Janus-like, duct-taped either to the front or back of her plastic bag–enshrouded head. Outfitted in garbage bags, in an artist-plus-model-plus-mother-plus-child vaudeville, she happily habituates as a hybrid.

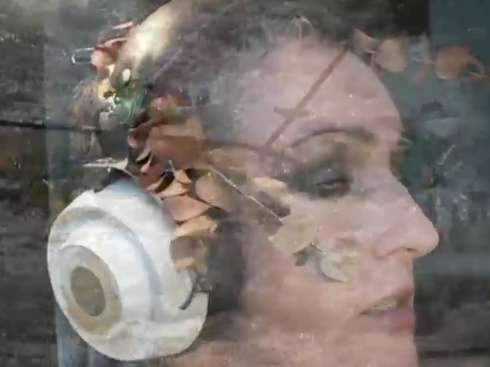

Fig. 5: Cheryl Donegan, Channeling in 4 Versions, 2001. Video, color, sound, 4:50 min. Courtesy the artist and

Electronic Arts Intermix (EAI), New York

Fig. 6: Cheryl Donegan, Stop Me If You Think You’ve Heard This One Before, 2008 (still). Video, color, sound, 21:07 min. trans. Sylvana Tomaselli (New York: W.W. Norton, 1991), 223.

SMASH THE MIRROR

In the four-part video installation Channeling (2001; Fig. 5), Donegan creates a

disorienting concatenation of metonymically fluent scenes in which avatars of the

artist abound. In the reframed fantasmatic scene from Tommy, “Smash the Mirror,”

Ann-Margret confronts her own image on TV in a scene of limitless jouissance.

The buckling and blistering image of the woman is how Donegan’s camera neither

captures nor conjures her—but both. The woman as mirage, evanescent, not all,

pas-toute.23 What is a woman in relationship to her image? Donegan shows, repeatedly, throughout her quest—Other to herself. The woman can only ever be

“channeled,” a conduit for representations: “That there is no sexual relationship, if

there’s one point at which this is [...] affirmed [...] it’s in the fact that we don’t know

what The Woman is. She’s an unknown entity—except, thank goodness, through

representations.”24 The bend-me-shape-me-anyway-you-want-me Mylar mutations of Channeling resemble Donegan’s “two great tastes that taste great together”25: brush-strokes and the plasticity of the video image. And not for nothing, the phallus, “as a reflection on a veil,”26 pervades the anamorphic quicksilver of Channeling.

File (2003; page 348): collage, montage, splice, shred, or shear, throw anything at the camera so as not to be caught by it. Bait for the eye. Garments, foil, fabric, postcards, pennants file past the camera, which we glimpse reflected intermittently, lost, too, amidst the drift of detritus. Shear All. Donegan in parts, her sliced-slipping-sliding body buoyed by, yet beyond, the surfaces. Amidst the shards and splinters of leftovers and litter, she is a remnant, superfluous, a lure. File is followed by Flushing (2004; page 350), a camera POV tour of the Flushing Mall in Queens, New York, which ramifies as an erratic détournement of a desolate consumer paradise. Strobe effects, buzzers, bells, split- and quartered-screens are deployed by Donegan to compose a visual ode to the obsolescence of a retail arcade and the dreams it bespoke. The audio is comprised mostly of misplaced or unanswered calls, including a child’s agitated demand, “Mommy, get that thing open! Get that thing open! Get that thing open!” Opening. Closing. Flushing: excitation, embarrassment, excreta—naming for the artist is not nothing.

After filing and flushing, she titles a work Cheryl (2005; page 352). Cheryl Hope is a self-motivational enthusiast, incessantly repeating cliché self-affirmations. Donegan does Cheryl one better by editing her self-promotional pronouncements to a succession of equally treacly dollar-store online images. The more Cheryl recites “I am...,” the more “I’m not” resounds. Her manic marketing mantra, “No doubt about it!,” is less a confirmation of Descartes’s cogito, than Lacan’s reformulation of it, “Either I am not thinking, or I am not.”27 Cheryl Hope constantly declares, confirms, or refutes the injunctions of late-capitalism on each isolated subject to promote their own brand. Donegan is not this Cheryl. But by a twist of the Mobius strip, she’s an assertion of Donegan’s logical artistic progression via a new iteration of her name. Through the Other Cheryl’s uncertain assertions, Donegan’s Cheryl discloses the division of the Other, and with it the “or worse...” of denying it. In letting Cheryl Hope speak hopelessly for herself, repeatedly, Cheryl Donegan allows the doubt that remains to accumulate, as a byproduct that exceeds the phallic measure.

REFUSES

Consistent with the logic that constitutes a series, Refuses (2006; page 356), which was inspired by Caroline Bergvall’s poem Fuses (after Carolee Schneemann), continues the metonymical drift of Cheryl. “Caroline’s poem reads like a ‘shot list’ of Carolee’s

film. I entered lines and words from the poem into search engines to try and rebuild

the film.”28 A profusion of dissonant images and clips salvaged from the internet,

punctuated with home-video excerpts and limned with neon-colored single frames

invade, recur, fracture, fuse, and disperse without a sound. Brutal and banal at once,

there is a pornographic pulsion to Donegan’s instrumentalization of the images.

Not all of what’s online—an infinite set—can be collected, collated, counted. Limitless.

Impossible. Less what we capture than what captures us. Punctum. Appointment. Object cause of desire.

While the biological father of her son Finnegan is absent in Stop Me If You Think You’ve Heard This One Before (2008; Fig. 6), the art-historical father Warhol is present; the puppet master, via not just the actress Viva, but also the ventriloquist Edgar Bergen’s dummy, Charlie McCarthy. With her son at her side, Donegan channels Viva’s rant from The Nude Restaurant. It’s expressly the point that we’ve heard this one before, and we couldn’t stop her if we tried! Spoken, not speaking, Donegan, medium-like, or possessed, portrays the speaking body. Like watching a Warhol double-screen projection, we’re witness to the dynamic between mother and son. Relay: in my acoustic drag, I’ll be your acoustic mirror. By acting out the voice and its affectations—the saying not the said—as Finnegan and the camera look on, Donegan stages a son’s encounter with his mother’s particular mode of enjoyment. The closing song, Martha and the Vandellas’ “Nowhere to Run,” pertains to both Cheryl and her boys. Motherhood, vented through Viva, the hippy daughter, is another guise of the woman. Midway, the work is flooded with images of rubbish caught in currents of rushing water.

I Still Want to Drown (2010; page 362) ciphers a desire to be swept away.

Dionne Warwick sings “Are You There (With Another Girl)” as Donegan intercuts

images of herself disrobing, à la Eyes Wide Shut, with voyeur-like scenes, shot

through a window, of Chantal Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman. Digital “fly-throughs”of

luxury real estate—ideal, spotless, antiseptic interiors—yield to hand-held shots of a suburban basement, wherein everything is in decay or decomposition, bric-a-brac, dried flowers, mementos. Too clean, too dirty, too little, too much, too near, too far. False choices. Something, as Donegan has consecutively shown, remains:

a surplus that exceeds the all or nothing of phallic calibration:

There exists a signifier that says something about femininity, the Phallus,

but it doesn’t say everything: there is a leftover of femininity about which

the signifier says nothing at all, but where the Vorstellungen come rushing

in—a whole series of representations. [...] The first point therefore is: there

is no signifier for the woman in the unconscious, but there are “images

and symbols” of woman—indeed, such images and symbols abound [...]

This is where we come to the second point [...] which tangibly complicates

the question further still: the Vorstellungen are not purely imaginary

elements. These semblants, these “images and symbols” that provide

a figure for femininity, put something in-form, right where the signifier is

missing; they are not simply illusory elements, elements of appearance:

they have very real effects.29

Footage of Cheryl on the morning segment of the Today Show, with the caption “Mall Madness”—beaming with pride, or is it hope?—concludes the tape. This is her momentary, singular solution to the fallacy of phallic logic. “The closing shots were shot off live television, depicting a woman modeling fall fashions—it is the artist. This was my first TV appearance, not as an artist, but as a model.”30 Shot off a television, depicting a woman.

BLOOD SUGAR

Set to a repeated riff from PJ Harvey’s “The Words That Maketh Murder,” Blood Sugar

(2013; Fig. 7) is a recycling sequence of models walking a starkly lit runway and young girls

in gowns flipping a mattress. Installed, the loop is projected on the back of a vintage

vinyl jacket; a screen that protects the body from the weather, and the eyes of others.

Fashion. Second skin. Yet, the title burrows beneath the skin. Metabolism. Pulse.

Life!Death!Blood!Sugar! What’s left? A disembodied woman’s sweater drops in slow

motion from a pedestal to a floor. Not before or behind the camera, neither artist nor

model—the artist has vaporized, non-localizable, remainder. Cheryl Donegan successively

shreds the repetitive logic of the universal phallic all to render a woman with the remnants

of the nonuniversal not all, byproducts with which others might know her by her true name:

shear all done again; and + or, “sure I’ll add on and gain.”31

Fig. 7: Cheryl Donegan, Blood Sugar, 2013 (still). Video, color, sound, 5:28 min. Courtesy the artist

Notes

1. Practisse is the title of one of Donegan’s video works from 1994.

2. See An Introductory Dictionary of Lacanian Psychoanalysis, Dylan Evans: “Lacan presents metonymy as a diachronic movement from one signifier to another along the signifying chain, as one signifier constantly refers to another in a perpetual deferral of meaning. Desire is also characterized by exactly the same never-ending process of continual deferral; since desire is ‘always desire

for something else,’ as soon as the object of desire is obtained, it is no longer desirable, and the subject’s desire fixes on another object. Thus Lacan writes that ‘desire is a metonymy,’” (Routledge, 1996), 114. And as Sadeq Rahimi explains: “The main differ-ence between metaphor and metonymy, according to Lacan, is that metaphor functions to suppress, while metonymy func-tions to combine. He writes: ‘It is in the word-to-word connection that metonymy is based,’ and then: ‘one word for another: that is the formula of metaphor.’” “The Unconscious: Metaphor and Metonymy,” Somatosphere, April 29, 2009 < http://somatosphere.net/2009/04/unconscious-metaphor-and-metonymy.html >(accessed on February 8, 2018).

3. As a video editor at Electronic Arts Intermix in the mid-1990s, I worked with Donegan on many of her post-single-take works.

4. Falling outside the scope of this essay are the six-second video loops Donegan posted to Vine, the social media video service, from the spring of 2014 until October 2016, when Twitter, the parent company, disabled uploads.

5. Lacan theorizes logical time in three stages, which occur inter-subjectively not objectively: the instant of seeing; the time for comprehending; the moment of concluding. This concept of

time anticipates his engagement with the linguist Ferdinand de Saussure’s distinction between the diachronic (temporal) and synchronic (atemporal) axes of language. With reference to the synchronic structure, Lacan affirms Freud’s assertion that the unconscious is atemporal. He will later add that it opens and closes. See Jacques Lacan, “Logical Time and the Assertion of Anticipated Certainty: A New Sophism,” The Ecrits, 161–75.

6. This is also the title of Donegan’s recent Kunsthalle Zürich exhibi-tion, and is a play on her Tumblr page.

7. Cheryl Donegan by Sam Korman, BOMB Magazine, Fall 2013 < https://bombmagazine.org/articles/cheryl-donegan/ > (accessed on February 6, 2018).

8. Given the length of the essay, I couldn’t pursue Donegan’s song selection and use of music. In addition to Sugar, bands and song-writers in her work include: Iggy and the Stooges, The Beach Boys, Yoko Ono, Erik Satie, The Smashing Pumpkins, Nazem El Ghazali, Bob Dylan, Bertolt Brecht, The Smiths, Wire, The Modern Lovers, The Ramones, Robert Wyatt, and The Who, among others.

9. Jacques Lacan, The Seminar of Jacques Lacan, Book VII: The

Ethics of Psychoanalysis, 1959–60, ed. Jacques-Alain Miller, trans.

Dennis Porter (New York: W.W. Norton, 1997), 129–30. See also

“Art After Lacan” by Francois Regnault < http://lacan.com/symp-tom14/art-after.html >.

10. iSpace was actually first coined by James Joyce in his 1939 book

Finnegans Wake.

11. See Jacques-Alain Miller, “A Fantasy,” August 2004 < http://2012.congresoamp.com/en/template.php?file=Textos/Conferencia-de-Jacques-Alain-Miller-en-Comandatuba.html > (accessed onFebruary 13, 2018).

12. Pierre-Gilles Guéguen, “Don’t Blame It On New York!,” 2009 <http://www.lacan.com/essays/?page_id=390> (accessed on February 6, 2018). “The lathouses that proliferate in the aletho-sphere are ‘false objects.’ These objects that are proposed to us ‘pretend to transport the same libido into the fetishism of mer-chandise as was extracted from it by the labour necessary to pro-duce or purchase them. [...] The lie about jouissance consists in making us forget [...] the particular circumstances of the extraction [of these objects] that will come to accompany the subject.’” From Éric Laurent, “Metamorphosis and Extraction of the Object in the Pragmatics of the Cure,” in Bulletin of the NLS, Issue 4, 2008, 12. For a definition of “alethosphere” see Jacques Lacan, The Seminar of Jacques Lacan, Book XVII: The Other Side of Psychoanalysis, 1969–70, ed. Jacques-Alain Miller, trans. Russell Grigg (New York: W.W. Norton, 2007), 150–63.

13. Jacques-Alain Miller addresses this in more detail: “We cannot fail to see that there has been a break, when Freud invented psycho-analysis under the aegis, as it were, of the reign of Queen Victoria, a paragon of the suppression of sexuality, whereas the twenty-first century is seeing the vast spread of what is called ‘porno,’ which amounts to coitus on show in a spectacle that is accessible to anyone on the web by means of a simple click of the mouse. From Victoria to porno, we have not only passed from prohibition to permission, but to incitation, intrusion, provocation, and forcing. What is pornography but a fantasy that has been filmed with enough variety to satisfy perverse appetites in all their diversity? There is no better indicator of the absence of sexual relation in the real than the imaginary profusion of the body as it devotes itself to being given and being taken.” From “The Uncon- scious and the Speaking Body,” < http://wapol.org/en/articulos/Template.asp?intTipoPagina=4&intPublicacion=13&intEdi-

cion=9&intIdiomaPublicacion=2&intArticulo=2742&intIdiomaAr-ticulo=2 > (accessed on February 6, 2018).

14. Jacques Lacan, The Seminar of Jacques Lacan, Book XI: The Four

Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis, ed. Jacques-Alain

Miller, trans. Alan Sheridan (New York/London: W.W. Norton and

Company, 1981), 84.

15. Indeed, it was Donegan who drew my attention to this in a phone

conversation, February 20, 2018.

16. Jacques Lacan, “Antigone between two deaths,” The Seminar

of Jacques Lacan, Book VII: The Ethics of Psychoanalysis, 1959-

1960, Chapter XXI, 270–83.

17. Elmer Peterson and Michel Sanouillet, ed., “The Creative Act,”

in Salt Seller: The Writings of Marcel Duchamp (Oxford University

Press, 1973), 139.

18. See Louis Menand, “Silence, Exile, Punning: James Joyce’s

chance encounters,” New Yorker, July 2, 2012.

19. Jacques Lacan, The Seminar of Jacques Lacan, Book XI: The Four

Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis, 103.

20. The title of her New Museum show was supposed to be Scenes +

Commercials, but the museum’s typeface didn’t have a “+” sign,

so they chose to go with “and” instead, which she was disappointed

about. From a conversation between the catalogue’s editor, Sarah

Stephenson, and Donegan after she had read a draft of this essay,

February 2018.

21. Created by Lacan, this neologism combines exterior and inti-

macy. Based on his axiom, “The unconscious is structured like a

language,” he asserts “the Other [i.e. language] whose primacy of

position Freud affirms in the form of something entfremdet, some-

thing strange to me, although it is at the heart of me.” The center

of the subject is therefore extrinsic to it, and the unconscious is

“outside.” The topology of the Möbius strip and torus illustrate the

extimate structure. See The Seminar of Jacques Lacan Book VII:

The Ethics of Psychoanalysis, 71.

22. In an email exchange with the author, Donegan explained, “It was

only with the The Janice Tapes that I started to edit on my own in

FCP...that was the first tape edited in digital.... I think I must have

shot on HI 8 and then digitized [in]...1999, around when Finn was

born...,” (November 8, 2017).

23. It’s the logic of the not-all, or nonuniversal, correlated with the rise

to the social zenith of the techno-science device-object, and its

instantaneous distribution of knowledge and enjoyment—and the

anxiety it produces—that imparts the future as feminine, non-binary,

and free of phallic logic. Not surprisingly, the Apple logo evokes Eve.

24. Jacques Lacan, Book XVI: D’un Autre à l’autre, 1968–69

(Paris: Seuil, 2006). Quoted in Geert Hoornaert, “Womanliness:

Defamation, Fantasy, Semblance,” in Hurly-Burly, Issue 5, 2010, 94.

25. Donegan in conversation with the author (June 19, 2017).

26. "This lack is beyond anything which can represent it. It is only ever

represented as a reflection on a veil.” Jacques Lacan, The Seminar

of Jacques Lacan, Book II: The Ego in Freud’s Theory and in the

Technique of Psychoanalysis, 1954–55, ed. Jacques-Alain Miller,

27. Jacques Lacan, Book XV: L'acte psychoanalytique, 1967-68, unpublished

28. Text message from the artist, February 15, 2018.

29. Hoornaert, “Womanliness: Defamation, Fantasy, Semblance,” 94–95.

30. Cheryl Donegan, “I Still Want to Drown” < https://www.eai.org/titles/i-still-want-to-drown > (accessed on February 8, 2018).

31. Text from the artist upon reading a draft of this essay, February 15, 2018.

Robert Buck © 2018

Download

.png)